With all this fuss about "Craft Beers" these days, it should be remembered that once upon a time New York City had quite a few breweries. Remember Miss Rheingold and "my beer is Rheingold the dry beer, think of Rheingold whenever you buy beer"? Does anyone remember Colonel Jacob Ruppert, his father's contributions to New York beer as well as his own role in creating one of the most revered

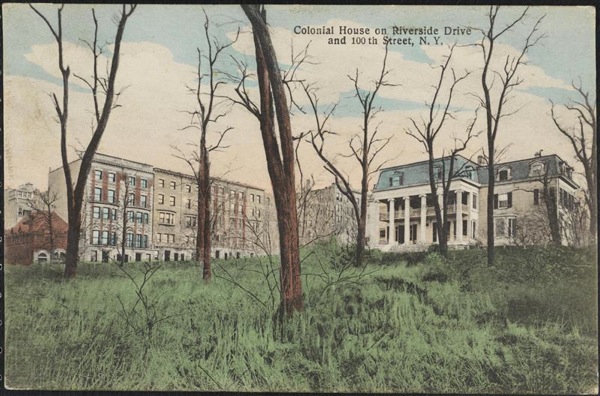

baseball teams ever or Rupperts beer? How about George Ehert, a german immigrant who dug 700 feet to create a well and who most beer historians believe to be the first great American brewer? And what about Peter Doelger whose mansion once stood on Riverside Drive at 100th Street? His brew was sold all over, including the saloon at 100th street and Broadway which is now home to the Metro Diner. And it won first prize!

Beer was as common centuries ago as it is now in this burg, it is just that there are more choices (go into any bodega, convience store or supermarket and you see why we live in the greatest country in the world - freedom of choice) and most of it is kept refrigerated. However once upon a time, before we had a clean, reliable drinking water system on this rock, very often beer was a safe bet in the early New Yorker's continuous game of avoiding Cholera. In fact, John Randel Jr., the surveyor who laid the grid upon the isle of Manhattan kept within his copious and precise notes a recipe for beer to be made while out in the field.

This is a section of the 1868 map showing 3 important items. One of course is the brewery. Two, the Aqueduct of the Croton sytem of 1842 turns at 107th and Amsterdam and heads south east and this raises yet another question. Was the Brewery getting water from the Croton system or an on-site well? And at the top of the map is a small space labeled Burying ground at what is now 110th Street and Columbus Avenue - practically right underneath Giovanni Pizza. Lion Brewing was a New York City - based brewery established in 1857; it closed in 1944.

Shortly after immigrating to New York, Catholic Bavarians August Schmid and Emanuel Bernheimer founded the Costanz Brewery at East 4th Street near Avenue B in 1850. The brewery produced a lagered beer, a favorite among German immigrants. By 1852, they built a second Costanz Brewery in Staten Island, home to a large German community. Finally after five years of success, in 1857 Bernheimer and Schmid establish the Lion Brewery.

At its peak, the Lion Brewery occupied about six city square blocks, from Central Park West to Amsterdam Avenue and from 107th to 109th Street. At the time Manhattan's Upper West Side was an open area with inexpensive land, housing, a few public institutions and an insane asylum. Although most of the population of what became Central Park had moved into what would become the Lincoln Center area (especially near what would become the 60th street yard of the New York Central's Hudson River Railroad) there were many people living on the Upper West Side in shanty's after being displaced in 1859. Consequently, with the brewery and surrounding areas, the Upper West Side failed to increase its real estate value until the early twentieth century.

This is a 1932 picture of 127 and 129 West 108th street. These two 3 story frame houses were right across the street from brewery. Although they were not Astor mansions, they are still nice houses. Were these structures connected to the brewery in some way? Management housing? Once upon a time people worked and lived in the same neighborhood. I have been told that they were the brew master's houses.

This is the map from 1898, the brewery has grown and the houses are on the map. The building labeled "Iron Works" is still there. It is one of the three garages on the block.

This is the 1911 map and clearly indicated are the two houses. 109th street is only slightly more developed. The brewery had it's own delivery service. There are two structures on the north side of 107th labeled "garage" (which are still there) as well as the old Iron Works now servings as a garage on 108th street. The undeveloped property surrounding the two houses is now a small playground dedicated to a local kid who had served in Vietnam.

Lion brewing got caught up in a wave of mergers and closings among some of the smaller New York Brewers in the early 1940s which continued until 1941, when the business closed. The brewery (including the canning facilities) was auctioned off on August 26, 1943. The plant was demolished in 1944 and more than 3,000 tons of steel were taken from the original brewery structure and recycled for the war effort and the lot was paved over. On Sundays, after the war, the returning WWII Veterans gathered there for a Softball League and played almost every Sunday afternoon. Home plate was located near 107th street and Columbus Avenue. Today the Booker T. Washington Middle School (we just called it "Booker T") occupies the Lion brewery's former location.

This is the Parish House of the Church of the Ascension. It can be said that this Roman Catholic church on 107th street is an out growth of the brewery; well it owes it's existence to the brewery at any rate. The brewery not only employed a large Catholic Bavarian population, the brewery sparked a large scale migration into the area surrounding the brewery of Catholic Barvarians in the mid - 19th century. For many years, Sunday services were held within the walls of the brewery for lack of a real church. Located at 221 West 107th Street the church that me and many others always referred to as just "Ascension" was established in 1895. Constructed between 1896 and 1897 the elaborate midblock church was designed by the firm of Schickel & Ditmars. The partners in this firm were of German descent and were awarded many projects, hired by other German - Americans. In addition to many private homes, they also produced a significant amount of work for the Catholic Church including Saint Monica's on East 79th Street, Church of St. Ignatius Loyola on Park Avenue at 83rd Street, part of St. Vincent's hospital and the "nobody steps on a church in my town" church - made famous by a colossal Stay Puff Marshmallow man in the picture Ghostbusters - the NYC Landmarked Holy Trinity Lutheran Church on 65th Street and Central Park West.