How many times have you walked the block on 102nd street between Broadway and Amsterdam and noticed 202 West 102nd and the odd angle it takes. If you stand on the north side of the street and look straight into the lobby of the building, you are facing real south, not downtown. Conversely, if you are coming out of the building you would be heading due north as you promenaded through the lobby. So why?

This building is at such an angle that it almost looks like a flat. The eastern wall in this garage follows the same contours that this building does.

This is the 1867 map and what appears to be Broadway is not, it is the Bloomingdale Road. The footprint of Broadway is visible to the west, or left, of the Road. As the Road takes a turn to head due north it is cutting, at an angle, through 102nd street. Today, where the road took that turn is in between Broadway and Amsterdam. At the top of the map where it says "Ward School" is the site of the playground outside P.S. 145. and is the first of what will eventually be 3 school buildings on the site.

This the 1885 map and The Boulevard is in place and it appears that The Road has been rendered obsolete. There are undeveloped lots now in the footprint of The Road and for some reason the lots on the south side follow the contours of the road. There is nothing on either side and still the abandoned Bloomingdale Road is dictating the shape of things to come.

This is the map from 1911 indicating the current 202 West 102nd street. Broadway is there in it's current location and the Road has been reduced to dotted lines with a blue tint and a building at an angle. The Hotel Clendining is there at 103rd and Amsterdam and the 442 seat Rose Theater east of Amsterdam showed movies until it closed around 1942. But was it showing movies in 1911?

“Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? . . . this is the time to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won’t all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes.” - Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Showing posts with label Upper West Side Manhattan. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Upper West Side Manhattan. Show all posts

Friday, March 28, 2014

Friday, March 21, 2014

THE NEW PROBLEM AND AN OLD SOLUTION

Once upon a time, in the 1980's, the ubiquitous corner market reared its head and became the thing we all dreaded when an older business with roots in the neighborhood and was replaced by the over priced fruit stand with dubious produce. Over time we have endured the proliferation of Duane Reades, banks, Starbucks and wireless stores along Broadway to the point where New York would start to look like the background in a Flintstones cartoon. The new business to over do it is the "Urgent Care" medical stores. If all human life were to disappear in flash, and aliens were to visit the empty earth, they would think that we were a bunch of coffee drinking, cell phone using money hoarders who where accident prone. This one is the straw that broke the my camel's back as it is going into the space once occupied by the late Great Shanghai.

This is the former home of the Great Shanghai. Soon it will be, by judging the pictures, a place for all those happy sick people.

The first listing of this culinary palace was in the New York Times. Jane Nickerson reviewed on August 1, 1956. How many Christmas Day dinners did you have there growing up, in what would become a staple for too many upper west side families from the 1960's through the late 70's?

"Away from Midtown and off the beaten track" Ms. Nickerson wrote while calling it a "roomy place". Owned by Shelia Chang who likes to help diners unfamiliar with Shanghai Cuisine make menu selections. When the place opened it had 3 menus - one Shanghai, one Cantonese and one American. The costs were approximated at $4 - $5 per person, not including drinks. There was a bar when you came in, along the right wall. The bartender was an older Caucasian man, as were the flies sitting at the bar. Once upon a time the space was a night club and I always wondered if this bartender was a holdover.

This is the Hotel Marseilles at some point in the 1920's. Designed by New York born and educated (Columbia School of Mines) Henry Allan Jacobs went to France after graduating in 1894 and attended (like too many other American architects did) the Ecole des Beaux- Arts. However he did very well while in attendance and was awarded the Prix de Rome. An early example of his work is the 1904 Seville Hotel at Madison Avenue and 29th Street. The entrance in the pictures above is visible on the right of this vintage postcard.

This is an ad for the fastest slice of Art Deco ever to cross the Atlantic, the Normandie. It was the ocean liner of all ocean liners. One of the most beautiful ships ever built, a product of the Roaring 20's if there ever was one. It attracted stars of the screen, stage, literary, artistic and financial worlds as the way to get to Europe.

This is the main dining room. It is sort of an art deco interpretation of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Fortunately it was not in it's home port when France fell in 1940. It became a possesion of the United States and was going to become the USS Lafayette.

On February 9th, 1942 work was proceeding on the Lafayette at pier 88 on the West Side. Some how a pile of life perservers caught fire and burnt the ship so badly and completely.

The fire was so bad that the 1000 foot long ship capsized under the weight of the water iused to suppress the fire.

Anything of value, anything that indicated the former

use of this ship had been removed. There were no art treasures lost. What was lost was a badly needed troopship and almost immediatly sabotage was suspected - union or otherwise.

In 1916 German saboteurs had plotted to blow up the Ansonia Hotel but that did not work out. What they did do was to blow up a rail yard in what is now Liberty State Park that was full of boxcars that were full of ammunition waiting to be loaded onto boats to be shipped to England during World War I. The arm holding the torch of the Statue of Liberty was shifted forward 4 feet and and the original plaster ceiling in the Great Hall of Ellis Island's immigration station fell (not the roof, just the interior ceiling). The result was the torch being closed off and a new ceiling in the Great Hall (made out of Gustivino Tiles. It also made Naval Intelligence wary of possible German sabotage here during the war years. But who could they turn to?

This guy. This is Salvatore Lucania, better known as Charles "Lucky" Luciano who had risen from the streets of lower Manhattan and became one of the most powerful men in organized criminal history, one of the creators of Las Vegas and the creator of the "5 Families" in New York. That division of labor solidified the the power of what he called "this thing of ours". Unfortunately on June 7, 1936, Luciano was convicted on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution (the only thing they could get him with?) and on July 18, 1936, Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison.

He was still running the show from his suite at the Maximum Security facility known as Dannemora by passing instructions to his underboss Vito Genovese. He was powerful outside but also inside. Through his efforts the only free standing church structure in the entire New York State prison system is at Dannemora, now known as Clinton Correction Facility. The Navy, the State of New York and Luciano's lawyers eventually concluded a deal. In exchange for a commutation of his sentence, Luciano promised his complete assistance even providing the U.S. military with mafia contacts in Sicily when the allied invaded in 1943. The deal was hammered out over a few meetings but at least one of those meetings took place in what was to become The Great Shanghai. After the deal was done, there was never a dockworker strike or another diabolical act of sabotage during the war. After the war Lucky was deported back to Sicily. He was a citizen of New York, but never an American citizen. I do not think he saw the difference.

This is the former home of the Great Shanghai. Soon it will be, by judging the pictures, a place for all those happy sick people.

The first listing of this culinary palace was in the New York Times. Jane Nickerson reviewed on August 1, 1956. How many Christmas Day dinners did you have there growing up, in what would become a staple for too many upper west side families from the 1960's through the late 70's?

This is the Hotel Marseilles at some point in the 1920's. Designed by New York born and educated (Columbia School of Mines) Henry Allan Jacobs went to France after graduating in 1894 and attended (like too many other American architects did) the Ecole des Beaux- Arts. However he did very well while in attendance and was awarded the Prix de Rome. An early example of his work is the 1904 Seville Hotel at Madison Avenue and 29th Street. The entrance in the pictures above is visible on the right of this vintage postcard.

This is the hotel as photographed by Irving Underhill in 1919. In the Business Records section of the New York Times on September 14th 1950 there was, among the Bankruptcy notices, reference to this night club. Nicholas Varadinoff, trading as the Dennis Restaurant and Bar, had finalized the bankruptcy of the business. Ironic - same last name, no relation. The hotel was sold numerous times, according to the Business Records sections of the times throughout the 1930's through 1946. After World War II, the hotel was used a refuge for displaced persons, survivors of the Holocaust. After that, as the tide turned in the area north of 96th, the hotel began it's downward slide into the 20th century equivalent of the legendary Old Brewery of the 5 Points. It was on this block that not only Humphrey Bogart became Humphrey Bogart, but also were William Burroughs bought heroin. It was in the hotel that Sarah Delano Roosevelt lived (but the neighborhood had become to Old - Testamenty for her old New York blue blood), it is where the writer Cornel Woolrich, the man who gave us Black Angel, The Bride Wore Black and what would become Rear Window lived (with his mother) from 1933 until 1957 (his last neighbors were one one side a prostitute and a junkie on the other). And it was probably in the restaurant / nightclub that a deal was hatched to spring a guy from Dannemora.

This is the main dining room. It is sort of an art deco interpretation of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Fortunately it was not in it's home port when France fell in 1940. It became a possesion of the United States and was going to become the USS Lafayette.

On February 9th, 1942 work was proceeding on the Lafayette at pier 88 on the West Side. Some how a pile of life perservers caught fire and burnt the ship so badly and completely.

The fire was so bad that the 1000 foot long ship capsized under the weight of the water iused to suppress the fire.

Anything of value, anything that indicated the former

use of this ship had been removed. There were no art treasures lost. What was lost was a badly needed troopship and almost immediatly sabotage was suspected - union or otherwise.

In 1916 German saboteurs had plotted to blow up the Ansonia Hotel but that did not work out. What they did do was to blow up a rail yard in what is now Liberty State Park that was full of boxcars that were full of ammunition waiting to be loaded onto boats to be shipped to England during World War I. The arm holding the torch of the Statue of Liberty was shifted forward 4 feet and and the original plaster ceiling in the Great Hall of Ellis Island's immigration station fell (not the roof, just the interior ceiling). The result was the torch being closed off and a new ceiling in the Great Hall (made out of Gustivino Tiles. It also made Naval Intelligence wary of possible German sabotage here during the war years. But who could they turn to?

This guy. This is Salvatore Lucania, better known as Charles "Lucky" Luciano who had risen from the streets of lower Manhattan and became one of the most powerful men in organized criminal history, one of the creators of Las Vegas and the creator of the "5 Families" in New York. That division of labor solidified the the power of what he called "this thing of ours". Unfortunately on June 7, 1936, Luciano was convicted on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution (the only thing they could get him with?) and on July 18, 1936, Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison.

He was still running the show from his suite at the Maximum Security facility known as Dannemora by passing instructions to his underboss Vito Genovese. He was powerful outside but also inside. Through his efforts the only free standing church structure in the entire New York State prison system is at Dannemora, now known as Clinton Correction Facility. The Navy, the State of New York and Luciano's lawyers eventually concluded a deal. In exchange for a commutation of his sentence, Luciano promised his complete assistance even providing the U.S. military with mafia contacts in Sicily when the allied invaded in 1943. The deal was hammered out over a few meetings but at least one of those meetings took place in what was to become The Great Shanghai. After the deal was done, there was never a dockworker strike or another diabolical act of sabotage during the war. After the war Lucky was deported back to Sicily. He was a citizen of New York, but never an American citizen. I do not think he saw the difference.

These are part of the doors to the main dining room on the Normandie. They were originally 20 feet tall. They are medallions are now the of Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Cathedral in Brooklyn.

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

Loew's 83rd - not 84th - a lost Thomas Lamb treasure on the Upper Westside

Opening in September 1921, the 2633 seat 83rd Street Theatre

was part of built at the same time as Loew’s State in Times Square. Built for MGM product and vaudeville, I

would venture to say that it was the premier Loew’s house north of Times Square

until the opening of the larger (by a 811 seats yet) Loew’s 175th

Street Wonder Theater in February of 1930. The State

and Loew’s Capital were the flagship uber-houses. The State was in the in the building that was home to Loew’s

corporate headquarters which in turn was the parent company of MGM. Until 1946 the big studios owned a

significant interest in theaters that bore their name. The Paramounts, Fox’s and

Warners of the world are examples of what became an anti-trust suit that was

finally settled after W.W. II and the studios were forced to divest. In the case of Loew’s, it was the other

way around. Exhibition had to

divest production as opposed to everyone else, production divesting their

exhibition interests. Don’t get me

wrong, there where loopholes and shenanigans to exploit.

The house has been referred to as plain. It was built just

before the real golden age of movie palace construction, which began around

1925 and came to a crashing halt by 1930.

It is nowhere near as ornate as other Lamb houses of the “golden era”

but it was beautiful. Although my

memories of the theater have severely faded, I do remember the stained glass

lighting fixtures flush with the overhang of the balcony.

However plain it might have been, Loew's did spring for new seats, as noted in this 1939 ad and the benefits of sponge foam. If I am remembering this right, there

was a chandelier over the inner lobby that had to be original. Many a time I had to wait for a date who

had gone into the ladies room but I had a view of that chandelier and the lobby

below from the balcony outside the restrooms.

Some of us remember the "matrons", older woman who had been hired during W.W.II to monitor the kids in the theaters. Children who came to these theaters by themselves had to sit in a special section. In the case of Loew's 83rd, the house right section of the orchestra (house left was for smoking). This was done to protect children from the raincoat men who would gravitate towards kids dropped off by their parents who, during the war, would go off and work in a defense plant for 8 hours and too many movie houses became day care centers.

The theater was first cut up into a “triplex” by 1975, then

a quad by 1978. The seats were never re-angled, left in their original single

screen position so you always sat at a slight angle from the screen. Until it

was cut up into a quad you had a view of the intact auditorium and it’s box

seats from the balcony. The fact

that the boxes were still there was not only a rarity but also shows how

theater design had changed. Live

entertainment, although included in the design had taken a secondary role in

the purpose of the theater, which was to show movies. The boxes, which did not have seats in them in 1975, were

used by patrons and did not interfere with the projection.

It also had an organ. Not a "Mighty Wurlitzer" but still a powerful instrument - not unlike an analog synthesizer (I know I have said this before). This is a picture of the second and last organ to be installed in the theater. Identical organs were installed in Loew's Alhambra Theatre in Brooklyn, Loew's Astoria Theatre in Queens, Loew's Spooner Theatre in the Bronx and Loew's Rio Theatre in Manhattan. The console pictured here was called the wing-style mahogany console.

Just before it was torn down I was fortunate enough to get a

tour of the remains of the orchestra section and the stage. Everything in front

of the wall they had put into make it a quad was intact. Sadly, however the

boxes had been removed as well as the decorative plaster above then. The orchestra pit had been covered over

years ago. The stage was very

large but was not used after the sound pictures and the depression really

kicked in. Loew’s dropped vaudeville in all but their big houses during the

depression. Even the big houses

had periods of time when their stages were dark. The Pin rail, used to tie off the ropes that hoisted scenery

up into the fly loft, was intact. There

was a white grand piano sitting in the middle of the stage. There were 4 or 5

floors of dressing rooms that I do not remember why I did not explore.

Loew’s 84th, the soulless "six-o-plex" opened in 1985

and for a few weeks the old 83rd Street theater operated at the same

time. There were a total of 10

screen on that block for while, a ten-o-plex. By

the summer of 1985, another Thomas Lamb theater was but a memory.

Friday, April 5, 2013

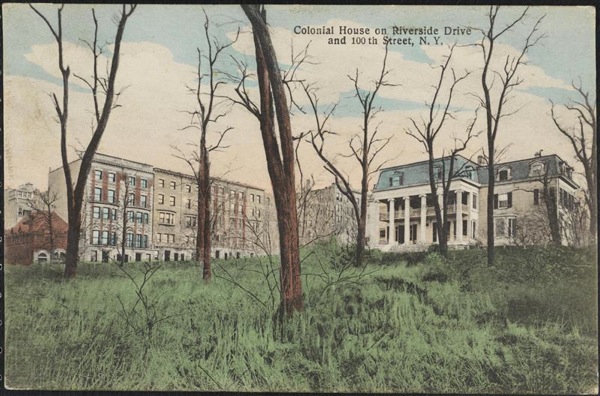

The Upper West Side's "Colonial House" in Color.

Often referred to as the "Colonial White House",probably because of the columns and the colorof the house, this mansion was important enough to merit it's own postcard. Built by the dry goods wholesaler William P. Furniss, the house was on land once owned by Charles Apthorpe. Apthorpe's estate once upon a time stretched from 99th street down to 81rst street, from Riverside Drive to Central Park West. In 1764 he sold a large chunk to Jacob Stryker. This piece included 96th street and the cove that used to be there was called Striker's Bay (spelling's and politician very often are corrupted. 100 years earlier the land was owned by Theunis Idens van Huyse, a Dutch tobacco farmer who once was the largest landowner on the island of Manhattan.

The Furniss estate briefly extended up to 104th street and Riverside Drive, and it did extend all the way to the edge of the Hudson River, but over the years lots were sold off or given away to his children and the construction of Riverside Drive cut off the river access. Furniss and his wife had passed away by 1880, their daughter Margaret sold the lots south of what is now 99th street to John N. A. Griswold of Newport, Rhode Island. Then in 1899 Griswold sold the lots, which had remained undeveloped during his ownership. This left a still ample piece of property for an already vastly different city from when the house first went up - the entire block from 99th street to 100th street from West End Avenue down to Riverside Drive.

This is a piece of the 1867 map and the house is clearly indicated on its eventual plot / block of land. On this map, the only indication that the estate stretched up to 104th street is a piece of property labeled "Furniss" on what is now the middle of West End Avenue at 103rd street down to the Bloomingdale Road / Broadway.

Eventually the old Furniss mansion had become an artist’s colony of sorts. A playwright by the name of Paul Kester lived in the house during its final years and would very often hold rehearsals in the big living room. Gertrude Stein lived in the Furniss house from February to late spring 1903. The Furniss house finally gave way to the ever growing city, apartment house construction and the old saying "the land is worth more than the house". The Old Colonial White House" was torn down in 1904.

The Furniss estate briefly extended up to 104th street and Riverside Drive, and it did extend all the way to the edge of the Hudson River, but over the years lots were sold off or given away to his children and the construction of Riverside Drive cut off the river access. Furniss and his wife had passed away by 1880, their daughter Margaret sold the lots south of what is now 99th street to John N. A. Griswold of Newport, Rhode Island. Then in 1899 Griswold sold the lots, which had remained undeveloped during his ownership. This left a still ample piece of property for an already vastly different city from when the house first went up - the entire block from 99th street to 100th street from West End Avenue down to Riverside Drive.

This is a piece of the 1867 map and the house is clearly indicated on its eventual plot / block of land. On this map, the only indication that the estate stretched up to 104th street is a piece of property labeled "Furniss" on what is now the middle of West End Avenue at 103rd street down to the Bloomingdale Road / Broadway.

Eventually the old Furniss mansion had become an artist’s colony of sorts. A playwright by the name of Paul Kester lived in the house during its final years and would very often hold rehearsals in the big living room. Gertrude Stein lived in the Furniss house from February to late spring 1903. The Furniss house finally gave way to the ever growing city, apartment house construction and the old saying "the land is worth more than the house". The Old Colonial White House" was torn down in 1904.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Riverside Drive at looking south from 109th street - nothing lasts forever in this town.

The future, and temporary Riverside Avenue, as it will be quickly renamed Riverside Drive. The Drive was under construction while lawsuits over land ownership and eminent domain abuse were litigated. One guess who won. This is looking south on September 30th 1870 from 109th Street. Obviously much has changed but there is so much that is recognizable today. None of the houses are with us but the shape of the island of greenery (the tangled mess of bushes and trees) between the service road and the main drive is starting to look familiar. The service road does not exist on the 1867 maps and neither do these houses. There are houses that unfortunately do not appear in this photo but do appear, along with their drive ways, on the 1867 map. What will become the service road is merely a suggestion at this point. The hill leading down from 106th street to the intersection of the service road and 108th street where the shortest timed traffic light on the west side is placed is already evident. Where the wagon with the big wheel in the middle of the drive is sitting is 108th street. In such a short period of time, massive change will happen.

Built in 1892 for Samuel Gamble Bayne (1844- 1924 ), the son of a prosperous merchant in the town Ramelton, Ireland. At the age of twenty-five Sam graduated from Queen's University Belfast and decided to travel to America. While he was here Samuel G. Bayne accumulated enough wealth to join the billionaires club. His wealth was based on gold prospecting in California, oil in Texas and banking; he was a founder of Seaboard National Bank, which ultimately after several mergers and acquisitions became what we all know and love today - Chase Manhattan Bank (now JP Morgan Chase). Could that be the nearly 80 year old Bayne sitting on the steps?

If his house was here still, if you crazy enough to have a car on this island and in this neighborhood, you would probably spend some time waiting for a green light in front of it. Not an unpleasant site to sit in front of.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Once there was a valley, Clendening Valley.

I love this print. Look how happy everyone appears to be; the mother with her parasol, the father in his best top hat strolling along holding his son's hand. The girl playing with a hoop and the couple promenading north on Second Avenue at 42nd Street in 1861 have an air of contentment. But the house up on that cliff looks precarious. As soon as Europeans showed up on Manahatta, the task of taming the island began. As the city grew in population and the boundary inched ever northward, more and more of the original landscape disappeared into oblivion in the name of progress. Forests felled, streams filled in, swamps drained and hills leveled. And when we imposed a grid upon the island, all of those streets, all of those right angles were cut through making the streets level. After all, it was a horse drawn world when the grid was being cut through those hills, and would it not be easier on the beasts if they had a level path. This scene was all too common and those streets that were cut through were very often muddy gullies, not the idyllic scene with a house that could fall over any second presented here. This is a great record of a great city undergoing yet another transformation. However some hills could not be tamed, especially if the word "valley" is attached. Manhattan Valley, where the subway was forced to come out of the ground as it dropped, only to go back into a tunnel as it rose again; and Clendening Valley which centered on Columbus Avenue approximately between 104th street all the way to 94th street with 96th street the bottom of the valley.

This is the Clendening Mansion. This print from Valentine's Manual lists the location as 90th Street and 8th Avenue. This is incorect. John "Lord" Clendening was a wealthy New Yorker who made his fortune importing Irish textiles after the Revolution, at the end of the 18th century. He built this lovely mansion, complete with widow's walk and waving American flag, around 1811. It stood at what is now the southwest corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, in the northern fringes of the area known as Bloomingdale. As the grew, so did the demand for a clean reliable water source. Early New Yorkers were incredibly dumb when it came to clean drinking water. They were very adept at polluting their water sources. Finally someone put it together and figured that all the garbage strewn ponds and wells (some wells too close to cemeteries that contained the bodies of those who had died in cholera epidemics) were killing them. Long story short, and it is a long story, after building the Erie Canal system nothing seemed impossible. So supervised by Chief Engineer John B Jervis (like in Port Jervis, who had served as one of the engineers of the Canal system) an aqueduct system was designed to bring water from reservoirs in Westchester County all the way down to City Hall Park. Bringing water by the force of gravity alone, New York City's first aqueduct system sent water 41 miles through stone aqueducts which for the most part were underground. Except in Clendening Valley. Because of the dip in the landscape a plan had to be hatched.

This is what they were going to look like. However the "Whig" party had gained control of the state legislature. This party was against wasting taxpayer money on arches through an aqueduct as they were firm believers in less government and lower taxes. They won their fight to scrap the idea of arches in favor of a solid wall of Manhattan Schist running the entire length of the valley. Realizing the obvious, an unbroken wall would be a barrier to development, in the first veto ever by a New York City mayor, Democrat Isaac Varian prevented the walling up of the valley . A compromise was reached and the wall was to passable in three places - at 98th, 99th, and 100th streets. The wall completely blocked the paths of the future 96th, 97th, and 101st Streets.

There are the arches on the map from 1868. The streets and sidewalks of 98th, 99th, and 100th streets passed beneath those arches. The Clendening estate stretched from the north side of 99th Street to the south side of 105th Street and from Central Park West to the Bloomingdale Road. The estate was lost in 1845 and the farm disappeared within 20 years. By the 1870s, development demanded more water; the above ground aqueduct section was buried underground into a pipe siphon and the solid wall blocking 96th, 97th, and 101st Streets–along with the arched 98th, 99th and 100th streets - was torn down.

Again, the map from 1868. The name John Clendening appears on the map although Clendening had lost the land years earlier. The diagonal line from where the aqueduct crosses west 105th street south west to just south of 103rd street and then west was called Clendening lane. The lane ran over to the plot of land that was the site of the old Downes Boulevard Hotel on 103rd street and the Boulevard (now Broadway). There are remnants of the intersection of the lane and the aqueduct on the south side of 105th street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues just east of P.S. 145. Best to observe it using bing or google maps.

This is looking northeast from just south of 101rst street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues. The 104th Street 9th Avenue El station is in the distance and the remains of the aqueduct through Clendening Valley are in the left foreground. This is quite possibly the remains of the arch-way at 101rst street. The original Croton Aqueduct, one of the most important pieces of what made New York City, opened June 22, 1842, taking 22 hours for gravity to move the water the 41 miles to Manhattan. Almost immediately it was woefully inadequate. Construction on a new aqueduct began in 1885. The new aqueduct, buried much deeper than the old one, went into service in 1890, with three times the capacity of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

Clendening lived on his rural estate for many years, but in 1836 he lost most of his money when President Andrew Jackson refused to renew the charter of the United States Bank, in which Clendening was a major stockholder. The estate was sold in 1845 as forty lots for a total of $4500. Although the mansion was torn down the area was known as Clendening Valley well into the post civil war 19th century New York. On the site where Lord Clendening's house one stood, the Clendening Hotel rose in its place on the west side of Amsterdam Avenue at 103rd street. The Hotel survived until 1965 when it was torn down for furthest west building of the Douglas Houses complex.

Thursday, March 7, 2013

West 107th and Riverside and it's connection to a castle up north.

On December 18th, 1937, the Karlopat Realty Company announced plans to build an apartment house on a rocky little lot at Riverside Drive and 107th Street. The townhouse next door, to the east, would go but there was a problem. The deed to the land came with a covenant which specified that a one family home must occupy the lot first before anything else was built. The idea behind this was probably a contextual zoning type of situation done by a private owner. The owner of the land did not want something sticking out like a sore thumb on such a beautiful stretch of Riverside Drive, not to mention the beautiful houses along 107th street. Seriously, why would you want to detract in anyway from the 12,000 square foot William Tuthill designed Morris Schinasi mansion. William Tuthill designed another New York City Landmark - Carnegie Hall. So what is the Karlopat Realty Company to do about this covenant? Build a house, but not just any house. A pre-fabricated structure from the National Houses, Inc. makers of Modern All-Steel house. House cost $3,000, and was built according to FHA specifications. Most significantly the house was designed by William Van Alen, architect of another New York City Landmark and art deco icon, the Chrysler Building. So once upon a time the intersection of 107th street and the Riverside Drive service road had an incredible architectural pedigree - a William Tuthill building and a William Van Alen building within feet of each other.

Karlopat Realty was part of an empire, the Paterno family. Charles Paterno along with his brothers Joseph, Michael, and Anthony left their mark on the upper west side like nobody else did. They were prolific builders, constructing some of the most beautiful non- Janes & Leo apartment houses. In Morningside Heights alone they were involved in the construction of 37 buildings. All over the upper west side and Morningside Heights there are buildings adorned with "P"for Paterno, or "JP" for Joseph Paterno(my childhood home does) or "PB" for Paterno Brothers.

This is a view of the family compound from the air. Today this site is occupied by Castle Village.

The fortune that was made built this castle for Charles Paterno. Like the Schinasi Mansion on 107th street, the castle also had an underground tunnel, in this case to Riverside Drive (now the north bound Henry Hudson Parkway) where there were stairs leading down to the hudson river. The Schinasi house tunnel went under the park to the not yet covered New York Central tracks, which ran along the shore of the river (pre - landfill).

How they got into this business has a most romantic tale, as told in Joseph Paterno's New York Times obituary. The young immigrant newsboy Joseph is shivering at his post on Park Row, watching a tall office building rise. "'Papa,' he asked, ' why do they make the business buildings so high?' ' Because it pays,' his father replied....'[T]his is the American way.' The bright-eyed newsboy wrinkled his brow and frowned, while making change for a customer. 'But, papa, if this is so why don't they make the houses and tenements high, too, as they will bring more rent?' The father smiled and patted his son's curly head. 'You have an eye for business, my son. Perhaps some day you may build some high houses.'" From that day on, the story continues, "it became Joseph's ambition to build skyscraper apartment houses."

The more accurate story is that their father Giovanni was in the real estate business and a builder back in the old country, Castelemezzano near Naples. Giovanni

left Italy after an earthquake destroyed a project he was financially involved

as well as building.

Charles Paterno

became Doctor Paterno when he graduated from Cornell Medical School in 1899. He was on his way to a career in medicine when fate intervened with the death of Giovanni. Doctor Charles Paterno,

fresh out of medical school, never practiced medicine, he and his brother Joesph took over his father's business and the result is all those "P's" on all those buildings.

The builders hired many architects who were from Italian and Jewish backgrounds, including Gaetan Ajello, Simon Schwartz, Arthur Gross, George and Edward Blum are among the names people did not see as the firms who got commissions on the east side. The more ethnic west side is one thing.

This beautiful vine drenched pergola wrapped along the edge of the cliff. The castle did not even last 40 years, the land became to valuable. In 1935 John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated the land that once was the C.K. Billings estate, Tryon Hall, to the City of New York to use as a park. Fort Tryon Park to be specific. The land values in the area began to rise and Charles Paterno smelled the future. In 1938 he announced plans to begin demolition of the castle in order to build 5 twelve story apartment houses called Castle Village.

This house is in the lower right corner of the shot from the air. I know nothing about this house, yet.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Elm Park, Elmwood, the Apthorpe Estate or as it is known now 91rst and Columbus Avenue.

This is looking north east from 100th street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues. The Ninth Avenue el looms over what is now called Columbus Avenue and the peaked roof of the 104th street station is clearly visible in upper left hand corner.

The large pile of rocks and stones in the lower right foreground is the remains of the original Croton Aqueduct of 1842. The aqueduct ran above ground and eventually to a receiving reservoir located between 86th and 79th streets and between 6th and 7th avenue. This area is now within Central Park and is the site of the Great Lawn. From there the water flowed through pipes to the distribution reservoir located between 41rst and 42nd streets, between 5th and 6th Avenues. The site is now occupied by the main branch of New York Public Library.

Eventually the above ground aqueduct was placed underground and the structure you see in the photo was rendered obsolete. The aqueduct was a hinderance to traffic flow on too many streets, and as soon as the aqueduct was no longer used, where it blocked a street it was knocked down. In many cases the stones were used in construction of other structures. Saint Paul the Apostle on 60th and 9th Avenue used a good deal of aqueduct chunks in it's construction.

This is an image of the the mansion built by successful merchant, loyalist and member of the Governors council (until 1783 when the British surrendered the colonies) Charles Apthorpe. The house, which was finally finished in 1764, was the center piece of a 268 acre estate called Elmwood. The house sat on a rise in the property so as to afford a view of the mighty Hudson River. 153 of the acres had been purchased from Oliver DeLancey (the street was named for his father Stephen who's property was once centered down there) who had a large piece of property that included a house on what is now 86th street and Riverside Drive. The house pictured stood at what became 91rst street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues.

This is a late 19th century map indicating that the structures of, or what is left of, Elmwood. At this point it is called Elm Park. One contemporary historian noted that “The once beautiful Apthorpe mansion now houses a beer and dance saloon.”

The 69th Regiment used the park as their review and drill grounds in 1855 and the grounds were used for a picnics and sporting contests.

However, it was the afternoon of July 12, 1870, that people remembered. On that day three thousand Irish Protestants were enjoying a picnic on the grounds of Elm Park. A mob of Irish Catholic laborers entered the park in what was to become known as the Orangeman Riots, killing five picnickers and injuring hundreds.

This is the house as it looked in 1891, just before it was demolished in favor of the ever encroaching city. The streets which ultimately cut through the property were laid out in 1811 and through out the post Civil War era those streets on a map became realities. There had been lanes going through the property, a wide lane lead from the house down to the old Bloomingdale Road and other smaller lanes cut through as well. Jauncey Lane and Striker's Lane were two lanes (that also served as property lines). Striker's Lane is significant as it is the name of the family that received a piece of the Apthorpe property after 1783 and was the name of the bay at what is now 96th street and Riverside Drive. The Striker's owned an inn on the bay and you can be sure that this lane lead right to the front door of Striker's Inn.

Another 1891 view. Apthorpe’s life was shattered with the outbreak of revolution. After the disastrous Battle of Long Island (really Brooklyn Heights) George Washington fled to Manhattan and up the Bloomingdale Road, a road that the British had laid out in 1703, to regroup, taking over the mansion as his headquarters. As soon as other American officers had moved their soldiers to Bloomingdale and the Elmwood estate, Washington moved on.

Within hours the British General Howe arrived, taking the mansion as his headquarters, remaining through the fighting of the Battle of Harlem Heights. Before the war was over, Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Cornwallis had also taken over the mansion.

With the final defeat of the British, Apthorpe was arrested and tried for high treason. For reasons never fully explained, he was released and permitted to keep most of his estate; although his sizable property in Massachusetts was confiscated.

On January 3, 1789 the mansion was the scene of the marriage of Apthorpe’s daughter to Congressional Delegate Hugh Williamson. Maria Apthorpe was described as “lovely and accomplished,” by the New York Daily Gazette. On April 4th 1789, the first Congress on The United States meets at the old Federal Hall (now the location of the Federal Hall National Memorial on Wall Street). This marriage says quid pro quo to me; in other words it would explain Apthorpe's release. Oliver DeLancey, Apthorpe's neighbor and a real thug (a rich boy thug - but a thug is a thug) lost everything and was deported to England.

The large pile of rocks and stones in the lower right foreground is the remains of the original Croton Aqueduct of 1842. The aqueduct ran above ground and eventually to a receiving reservoir located between 86th and 79th streets and between 6th and 7th avenue. This area is now within Central Park and is the site of the Great Lawn. From there the water flowed through pipes to the distribution reservoir located between 41rst and 42nd streets, between 5th and 6th Avenues. The site is now occupied by the main branch of New York Public Library.

Eventually the above ground aqueduct was placed underground and the structure you see in the photo was rendered obsolete. The aqueduct was a hinderance to traffic flow on too many streets, and as soon as the aqueduct was no longer used, where it blocked a street it was knocked down. In many cases the stones were used in construction of other structures. Saint Paul the Apostle on 60th and 9th Avenue used a good deal of aqueduct chunks in it's construction.

This is an image of the the mansion built by successful merchant, loyalist and member of the Governors council (until 1783 when the British surrendered the colonies) Charles Apthorpe. The house, which was finally finished in 1764, was the center piece of a 268 acre estate called Elmwood. The house sat on a rise in the property so as to afford a view of the mighty Hudson River. 153 of the acres had been purchased from Oliver DeLancey (the street was named for his father Stephen who's property was once centered down there) who had a large piece of property that included a house on what is now 86th street and Riverside Drive. The house pictured stood at what became 91rst street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues.

This is a late 19th century map indicating that the structures of, or what is left of, Elmwood. At this point it is called Elm Park. One contemporary historian noted that “The once beautiful Apthorpe mansion now houses a beer and dance saloon.”

The 69th Regiment used the park as their review and drill grounds in 1855 and the grounds were used for a picnics and sporting contests.

However, it was the afternoon of July 12, 1870, that people remembered. On that day three thousand Irish Protestants were enjoying a picnic on the grounds of Elm Park. A mob of Irish Catholic laborers entered the park in what was to become known as the Orangeman Riots, killing five picnickers and injuring hundreds.

This is the house as it looked in 1891, just before it was demolished in favor of the ever encroaching city. The streets which ultimately cut through the property were laid out in 1811 and through out the post Civil War era those streets on a map became realities. There had been lanes going through the property, a wide lane lead from the house down to the old Bloomingdale Road and other smaller lanes cut through as well. Jauncey Lane and Striker's Lane were two lanes (that also served as property lines). Striker's Lane is significant as it is the name of the family that received a piece of the Apthorpe property after 1783 and was the name of the bay at what is now 96th street and Riverside Drive. The Striker's owned an inn on the bay and you can be sure that this lane lead right to the front door of Striker's Inn.

Another 1891 view. Apthorpe’s life was shattered with the outbreak of revolution. After the disastrous Battle of Long Island (really Brooklyn Heights) George Washington fled to Manhattan and up the Bloomingdale Road, a road that the British had laid out in 1703, to regroup, taking over the mansion as his headquarters. As soon as other American officers had moved their soldiers to Bloomingdale and the Elmwood estate, Washington moved on.

Within hours the British General Howe arrived, taking the mansion as his headquarters, remaining through the fighting of the Battle of Harlem Heights. Before the war was over, Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Cornwallis had also taken over the mansion.

With the final defeat of the British, Apthorpe was arrested and tried for high treason. For reasons never fully explained, he was released and permitted to keep most of his estate; although his sizable property in Massachusetts was confiscated.

On January 3, 1789 the mansion was the scene of the marriage of Apthorpe’s daughter to Congressional Delegate Hugh Williamson. Maria Apthorpe was described as “lovely and accomplished,” by the New York Daily Gazette. On April 4th 1789, the first Congress on The United States meets at the old Federal Hall (now the location of the Federal Hall National Memorial on Wall Street). This marriage says quid pro quo to me; in other words it would explain Apthorpe's release. Oliver DeLancey, Apthorpe's neighbor and a real thug (a rich boy thug - but a thug is a thug) lost everything and was deported to England.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

The Riviera Theatre

The Riviera, behind the orchestra section.

The screen is lit quite possibly by footlights. I have often wondered if they were original. The red curtains cover the damage done by the removal of the boxes. The Riverside had some sort of lighting on the stage at this point as evidenced in the pictures below, not the case with the Riviera. Both houses underwent renovations in the 1950's. It was at this time that the Skouras Brothers owned the theaters.

The brothers Skouras started in St. Louis in distribution and exhibition and eventually went into production. Spyros Skouras became prsident of 20th Century Fox in 1942 and was instrumental in introducing Cinemascope. With this new wide screen process came the removal of boxes in many theaters across the country. Somewhere there is a pile of old discarded boxes.

The Skouras brothers were notorious "modernizers". As you can see in these photos, there are not only no more boxes but no more orchestra pits as well. Very often orchestra pits were covered over to add an extra row or two of seats. In some cases, the Mighty Wurlitzer (or similar organ) would be left on it's lift, at the basement level, covered over by concrete slabs. Although there were multiple organ (Wurlitzer and Morton) installations at both the Riverside and Riviera, I am not sure what happened to them or where they ended up. I do know that the organ up in the Japanese Gardens was abandoned and vandalized.

This is the mural on the sound board above the proscenium arch. Due to the terrible lighting it is hard to make out what it represents in this picture.

I read a story written by the man who took these photos. His real quest that day was to not only photograph these two theaters but also to photograph the Japanese Gardens above the Riviera. The two elevators that went up there were had been out of commission for years. The stair case that went up to the Gardens from the elevator lobby had been sealed off long ago. According to the floor plans for the Riviera Building, there were no connections between the theaters and the office building. The only way they found to get into the Japanese Gardens was through 5 floors of Riviera dressing rooms, described as dark, dank and musty.

This is a digitally enhanced picture. Obviously, demolition has begun. The lighting in this case is mostly natural light. The mural on the sound board appears to be one of those life at Versailles pastoral images. Very Rococo. This mural, along with the murals in the Riverside, were probably not saved. This was in the pre-Urban Archeology days and nothing was saved or recycled.

I digitally enhanced this picture as well. Once I scanned these pictures into my iPhoto, I became convinced that there was more to the pictures than what I was seeing.

Demolition on the Riviera began close to ten years after the collapse of the Riverside. The site, which almost played host to Gimbel's West, was a garden for many years. When the building that eventually went up on the site was built, the displaced garden moved to Riverside Park as is called the Community Garden.

This is the un - enhanced, original version of the above picture. The theaters were photographed as discussion about their demise was bandied about. Alexanders had expressed a great deal of interest in the site for a new store, apartment tower and new single screen theater. Gimbel's had offered pretty much the same deal. However, neighborhood opposition to creating an overwhelmingly commercial area, at 96th and Broadway, scaled back the development to a 30 story tower of studios and one bedrooms (to meet the need of an ever growing swinging singles segment of society since the city was attracting a younger, less family oriented population and families were moving to the suburbs - or so the developer believed). However, there were a few cries about preservation, maybe 4.

The wood frame structure on the stage was probably for the movie screen. The speaker horns are clearly visible behind the wooden frame. Again this is an enhanced picture.

This is a digitally enhanced view of the stage. I do not believe that these photos were taken by the photographer of the "before" pictures. He was just an enthusiastic amateur theater historian, as far as I can tell, and the condition of the Riviera looks precarious.

In an earlier post, I cryptically stated that after the Riverside collapsed and emergency personnel had dug through the debris for days, that no bodies were found - at that time. The two theaters were built a year apart, the Riverside (which had a longer construction period) in opening in 1912 and The Riviera in 1913, and were entirely separate buildings. There were connections made in the basement years later and it was during the demolition of the Riviera that,according to local legend and lore, two bodies were found in what was left of a connector passage between the still standing Riviera and the no longer with us Riverside.

The last of the Riviera. "We will be judged not by what we have built, but by what we have destroyed" said the New York Times in an editorial about the destruction of the old Pennsylvania Station. How sad and true. The site, now the home to one of the least attractive buildings on the upper west side, was once an elegant entertainment complex that could seat almost 5000 at any given moment was certainly a gift. The entire complex was designed by Thomas Lamb, who also designed the Eltinge.

The screen is lit quite possibly by footlights. I have often wondered if they were original. The red curtains cover the damage done by the removal of the boxes. The Riverside had some sort of lighting on the stage at this point as evidenced in the pictures below, not the case with the Riviera. Both houses underwent renovations in the 1950's. It was at this time that the Skouras Brothers owned the theaters.

The brothers Skouras started in St. Louis in distribution and exhibition and eventually went into production. Spyros Skouras became prsident of 20th Century Fox in 1942 and was instrumental in introducing Cinemascope. With this new wide screen process came the removal of boxes in many theaters across the country. Somewhere there is a pile of old discarded boxes.

The Skouras brothers were notorious "modernizers". As you can see in these photos, there are not only no more boxes but no more orchestra pits as well. Very often orchestra pits were covered over to add an extra row or two of seats. In some cases, the Mighty Wurlitzer (or similar organ) would be left on it's lift, at the basement level, covered over by concrete slabs. Although there were multiple organ (Wurlitzer and Morton) installations at both the Riverside and Riviera, I am not sure what happened to them or where they ended up. I do know that the organ up in the Japanese Gardens was abandoned and vandalized.

This is the mural on the sound board above the proscenium arch. Due to the terrible lighting it is hard to make out what it represents in this picture.

I read a story written by the man who took these photos. His real quest that day was to not only photograph these two theaters but also to photograph the Japanese Gardens above the Riviera. The two elevators that went up there were had been out of commission for years. The stair case that went up to the Gardens from the elevator lobby had been sealed off long ago. According to the floor plans for the Riviera Building, there were no connections between the theaters and the office building. The only way they found to get into the Japanese Gardens was through 5 floors of Riviera dressing rooms, described as dark, dank and musty.

This is a digitally enhanced picture. Obviously, demolition has begun. The lighting in this case is mostly natural light. The mural on the sound board appears to be one of those life at Versailles pastoral images. Very Rococo. This mural, along with the murals in the Riverside, were probably not saved. This was in the pre-Urban Archeology days and nothing was saved or recycled.

I digitally enhanced this picture as well. Once I scanned these pictures into my iPhoto, I became convinced that there was more to the pictures than what I was seeing.

Demolition on the Riviera began close to ten years after the collapse of the Riverside. The site, which almost played host to Gimbel's West, was a garden for many years. When the building that eventually went up on the site was built, the displaced garden moved to Riverside Park as is called the Community Garden.

This is the un - enhanced, original version of the above picture. The theaters were photographed as discussion about their demise was bandied about. Alexanders had expressed a great deal of interest in the site for a new store, apartment tower and new single screen theater. Gimbel's had offered pretty much the same deal. However, neighborhood opposition to creating an overwhelmingly commercial area, at 96th and Broadway, scaled back the development to a 30 story tower of studios and one bedrooms (to meet the need of an ever growing swinging singles segment of society since the city was attracting a younger, less family oriented population and families were moving to the suburbs - or so the developer believed). However, there were a few cries about preservation, maybe 4.

The wood frame structure on the stage was probably for the movie screen. The speaker horns are clearly visible behind the wooden frame. Again this is an enhanced picture.

This is a digitally enhanced view of the stage. I do not believe that these photos were taken by the photographer of the "before" pictures. He was just an enthusiastic amateur theater historian, as far as I can tell, and the condition of the Riviera looks precarious.

In an earlier post, I cryptically stated that after the Riverside collapsed and emergency personnel had dug through the debris for days, that no bodies were found - at that time. The two theaters were built a year apart, the Riverside (which had a longer construction period) in opening in 1912 and The Riviera in 1913, and were entirely separate buildings. There were connections made in the basement years later and it was during the demolition of the Riviera that,according to local legend and lore, two bodies were found in what was left of a connector passage between the still standing Riviera and the no longer with us Riverside.

The last of the Riviera. "We will be judged not by what we have built, but by what we have destroyed" said the New York Times in an editorial about the destruction of the old Pennsylvania Station. How sad and true. The site, now the home to one of the least attractive buildings on the upper west side, was once an elegant entertainment complex that could seat almost 5000 at any given moment was certainly a gift. The entire complex was designed by Thomas Lamb, who also designed the Eltinge.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)