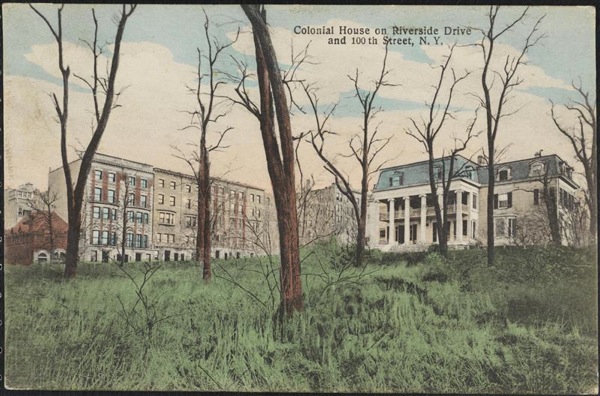

Often referred to as the "Colonial White House",probably because of the columns and the colorof the house, this mansion was important enough to merit it's own postcard. Built by the dry goods wholesaler William P. Furniss, the house was on land once owned by Charles Apthorpe. Apthorpe's estate once upon a time stretched from 99th street down to 81rst street, from Riverside Drive to Central Park West. In 1764 he sold a large chunk to Jacob Stryker. This piece included 96th street and the cove that used to be there was called Striker's Bay (spelling's and politician very often are corrupted. 100 years earlier the land was owned by Theunis Idens van Huyse, a Dutch tobacco farmer who once was the largest landowner on the island of Manhattan.

The Furniss estate briefly extended up to 104th street and Riverside Drive, and it did extend all the way to the edge of the Hudson River, but over the years lots were sold off or given away to his children and the construction of Riverside Drive cut off the river access. Furniss and his wife had passed away by 1880, their daughter

Margaret sold the lots south of what is now 99th street to John N. A. Griswold of Newport,

Rhode Island. Then in 1899 Griswold sold the lots, which had remained

undeveloped during his ownership. This left a still ample piece of property for an already vastly different city from when the house first went up - the entire block from 99th street to 100th street from West End Avenue down to Riverside Drive.

This is a piece of the 1867 map and the house is clearly indicated on its eventual plot / block of land. On this map, the only indication that the estate stretched up to 104th street is a piece of property labeled "Furniss" on what is now the middle of West End Avenue at 103rd street down to the Bloomingdale Road / Broadway.

Eventually the old Furniss mansion had become an artist’s colony of

sorts. A playwright by the name of Paul Kester lived in the house during its final years

and would very often hold rehearsals in the big living room. Gertrude

Stein lived in the Furniss house from

February to late spring 1903. The Furniss house finally gave way to the ever growing city, apartment house construction and the old saying "the land is worth more than the house". The Old Colonial White House" was torn down in 1904.

“Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? . . . this is the time to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won’t all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes.” - Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Friday, April 5, 2013

Friday, March 22, 2013

Riverside Drive at looking south from 109th street - nothing lasts forever in this town.

The future, and temporary Riverside Avenue, as it will be quickly renamed Riverside Drive. The Drive was under construction while lawsuits over land ownership and eminent domain abuse were litigated. One guess who won. This is looking south on September 30th 1870 from 109th Street. Obviously much has changed but there is so much that is recognizable today. None of the houses are with us but the shape of the island of greenery (the tangled mess of bushes and trees) between the service road and the main drive is starting to look familiar. The service road does not exist on the 1867 maps and neither do these houses. There are houses that unfortunately do not appear in this photo but do appear, along with their drive ways, on the 1867 map. What will become the service road is merely a suggestion at this point. The hill leading down from 106th street to the intersection of the service road and 108th street where the shortest timed traffic light on the west side is placed is already evident. Where the wagon with the big wheel in the middle of the drive is sitting is 108th street. In such a short period of time, massive change will happen.

Built in 1892 for Samuel Gamble Bayne (1844- 1924 ), the son of a prosperous merchant in the town Ramelton, Ireland. At the age of twenty-five Sam graduated from Queen's University Belfast and decided to travel to America. While he was here Samuel G. Bayne accumulated enough wealth to join the billionaires club. His wealth was based on gold prospecting in California, oil in Texas and banking; he was a founder of Seaboard National Bank, which ultimately after several mergers and acquisitions became what we all know and love today - Chase Manhattan Bank (now JP Morgan Chase). Could that be the nearly 80 year old Bayne sitting on the steps?

If his house was here still, if you crazy enough to have a car on this island and in this neighborhood, you would probably spend some time waiting for a green light in front of it. Not an unpleasant site to sit in front of.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Once there was a valley, Clendening Valley.

I love this print. Look how happy everyone appears to be; the mother with her parasol, the father in his best top hat strolling along holding his son's hand. The girl playing with a hoop and the couple promenading north on Second Avenue at 42nd Street in 1861 have an air of contentment. But the house up on that cliff looks precarious. As soon as Europeans showed up on Manahatta, the task of taming the island began. As the city grew in population and the boundary inched ever northward, more and more of the original landscape disappeared into oblivion in the name of progress. Forests felled, streams filled in, swamps drained and hills leveled. And when we imposed a grid upon the island, all of those streets, all of those right angles were cut through making the streets level. After all, it was a horse drawn world when the grid was being cut through those hills, and would it not be easier on the beasts if they had a level path. This scene was all too common and those streets that were cut through were very often muddy gullies, not the idyllic scene with a house that could fall over any second presented here. This is a great record of a great city undergoing yet another transformation. However some hills could not be tamed, especially if the word "valley" is attached. Manhattan Valley, where the subway was forced to come out of the ground as it dropped, only to go back into a tunnel as it rose again; and Clendening Valley which centered on Columbus Avenue approximately between 104th street all the way to 94th street with 96th street the bottom of the valley.

This is the Clendening Mansion. This print from Valentine's Manual lists the location as 90th Street and 8th Avenue. This is incorect. John "Lord" Clendening was a wealthy New Yorker who made his fortune importing Irish textiles after the Revolution, at the end of the 18th century. He built this lovely mansion, complete with widow's walk and waving American flag, around 1811. It stood at what is now the southwest corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, in the northern fringes of the area known as Bloomingdale. As the grew, so did the demand for a clean reliable water source. Early New Yorkers were incredibly dumb when it came to clean drinking water. They were very adept at polluting their water sources. Finally someone put it together and figured that all the garbage strewn ponds and wells (some wells too close to cemeteries that contained the bodies of those who had died in cholera epidemics) were killing them. Long story short, and it is a long story, after building the Erie Canal system nothing seemed impossible. So supervised by Chief Engineer John B Jervis (like in Port Jervis, who had served as one of the engineers of the Canal system) an aqueduct system was designed to bring water from reservoirs in Westchester County all the way down to City Hall Park. Bringing water by the force of gravity alone, New York City's first aqueduct system sent water 41 miles through stone aqueducts which for the most part were underground. Except in Clendening Valley. Because of the dip in the landscape a plan had to be hatched.

This is what they were going to look like. However the "Whig" party had gained control of the state legislature. This party was against wasting taxpayer money on arches through an aqueduct as they were firm believers in less government and lower taxes. They won their fight to scrap the idea of arches in favor of a solid wall of Manhattan Schist running the entire length of the valley. Realizing the obvious, an unbroken wall would be a barrier to development, in the first veto ever by a New York City mayor, Democrat Isaac Varian prevented the walling up of the valley . A compromise was reached and the wall was to passable in three places - at 98th, 99th, and 100th streets. The wall completely blocked the paths of the future 96th, 97th, and 101st Streets.

There are the arches on the map from 1868. The streets and sidewalks of 98th, 99th, and 100th streets passed beneath those arches. The Clendening estate stretched from the north side of 99th Street to the south side of 105th Street and from Central Park West to the Bloomingdale Road. The estate was lost in 1845 and the farm disappeared within 20 years. By the 1870s, development demanded more water; the above ground aqueduct section was buried underground into a pipe siphon and the solid wall blocking 96th, 97th, and 101st Streets–along with the arched 98th, 99th and 100th streets - was torn down.

Again, the map from 1868. The name John Clendening appears on the map although Clendening had lost the land years earlier. The diagonal line from where the aqueduct crosses west 105th street south west to just south of 103rd street and then west was called Clendening lane. The lane ran over to the plot of land that was the site of the old Downes Boulevard Hotel on 103rd street and the Boulevard (now Broadway). There are remnants of the intersection of the lane and the aqueduct on the south side of 105th street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues just east of P.S. 145. Best to observe it using bing or google maps.

This is looking northeast from just south of 101rst street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues. The 104th Street 9th Avenue El station is in the distance and the remains of the aqueduct through Clendening Valley are in the left foreground. This is quite possibly the remains of the arch-way at 101rst street. The original Croton Aqueduct, one of the most important pieces of what made New York City, opened June 22, 1842, taking 22 hours for gravity to move the water the 41 miles to Manhattan. Almost immediately it was woefully inadequate. Construction on a new aqueduct began in 1885. The new aqueduct, buried much deeper than the old one, went into service in 1890, with three times the capacity of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

Clendening lived on his rural estate for many years, but in 1836 he lost most of his money when President Andrew Jackson refused to renew the charter of the United States Bank, in which Clendening was a major stockholder. The estate was sold in 1845 as forty lots for a total of $4500. Although the mansion was torn down the area was known as Clendening Valley well into the post civil war 19th century New York. On the site where Lord Clendening's house one stood, the Clendening Hotel rose in its place on the west side of Amsterdam Avenue at 103rd street. The Hotel survived until 1965 when it was torn down for furthest west building of the Douglas Houses complex.

Thursday, March 7, 2013

West 107th and Riverside and it's connection to a castle up north.

On December 18th, 1937, the Karlopat Realty Company announced plans to build an apartment house on a rocky little lot at Riverside Drive and 107th Street. The townhouse next door, to the east, would go but there was a problem. The deed to the land came with a covenant which specified that a one family home must occupy the lot first before anything else was built. The idea behind this was probably a contextual zoning type of situation done by a private owner. The owner of the land did not want something sticking out like a sore thumb on such a beautiful stretch of Riverside Drive, not to mention the beautiful houses along 107th street. Seriously, why would you want to detract in anyway from the 12,000 square foot William Tuthill designed Morris Schinasi mansion. William Tuthill designed another New York City Landmark - Carnegie Hall. So what is the Karlopat Realty Company to do about this covenant? Build a house, but not just any house. A pre-fabricated structure from the National Houses, Inc. makers of Modern All-Steel house. House cost $3,000, and was built according to FHA specifications. Most significantly the house was designed by William Van Alen, architect of another New York City Landmark and art deco icon, the Chrysler Building. So once upon a time the intersection of 107th street and the Riverside Drive service road had an incredible architectural pedigree - a William Tuthill building and a William Van Alen building within feet of each other.

Karlopat Realty was part of an empire, the Paterno family. Charles Paterno along with his brothers Joseph, Michael, and Anthony left their mark on the upper west side like nobody else did. They were prolific builders, constructing some of the most beautiful non- Janes & Leo apartment houses. In Morningside Heights alone they were involved in the construction of 37 buildings. All over the upper west side and Morningside Heights there are buildings adorned with "P"for Paterno, or "JP" for Joseph Paterno(my childhood home does) or "PB" for Paterno Brothers.

This is a view of the family compound from the air. Today this site is occupied by Castle Village.

The fortune that was made built this castle for Charles Paterno. Like the Schinasi Mansion on 107th street, the castle also had an underground tunnel, in this case to Riverside Drive (now the north bound Henry Hudson Parkway) where there were stairs leading down to the hudson river. The Schinasi house tunnel went under the park to the not yet covered New York Central tracks, which ran along the shore of the river (pre - landfill).

How they got into this business has a most romantic tale, as told in Joseph Paterno's New York Times obituary. The young immigrant newsboy Joseph is shivering at his post on Park Row, watching a tall office building rise. "'Papa,' he asked, ' why do they make the business buildings so high?' ' Because it pays,' his father replied....'[T]his is the American way.' The bright-eyed newsboy wrinkled his brow and frowned, while making change for a customer. 'But, papa, if this is so why don't they make the houses and tenements high, too, as they will bring more rent?' The father smiled and patted his son's curly head. 'You have an eye for business, my son. Perhaps some day you may build some high houses.'" From that day on, the story continues, "it became Joseph's ambition to build skyscraper apartment houses."

The more accurate story is that their father Giovanni was in the real estate business and a builder back in the old country, Castelemezzano near Naples. Giovanni

left Italy after an earthquake destroyed a project he was financially involved

as well as building.

Charles Paterno

became Doctor Paterno when he graduated from Cornell Medical School in 1899. He was on his way to a career in medicine when fate intervened with the death of Giovanni. Doctor Charles Paterno,

fresh out of medical school, never practiced medicine, he and his brother Joesph took over his father's business and the result is all those "P's" on all those buildings.

The builders hired many architects who were from Italian and Jewish backgrounds, including Gaetan Ajello, Simon Schwartz, Arthur Gross, George and Edward Blum are among the names people did not see as the firms who got commissions on the east side. The more ethnic west side is one thing.

This beautiful vine drenched pergola wrapped along the edge of the cliff. The castle did not even last 40 years, the land became to valuable. In 1935 John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated the land that once was the C.K. Billings estate, Tryon Hall, to the City of New York to use as a park. Fort Tryon Park to be specific. The land values in the area began to rise and Charles Paterno smelled the future. In 1938 he announced plans to begin demolition of the castle in order to build 5 twelve story apartment houses called Castle Village.

This house is in the lower right corner of the shot from the air. I know nothing about this house, yet.

Thursday, February 14, 2013

More Riverside Theater

This is the standard early 1920's program cover for the Keith circuit. I found another east coast theater using the same art work on the program cover, the Orpheum (in Boston I believe) that was proud to be presenting Houdini live on stage. What a smart couple, all dressed up for an evening at the Riverside.

At the time of this programs publication composer and bandleader Julius Lenzberg was the orchestra leader at the Riverside. This is the Riverside Orchestra, Julius is the guy with the violin. Born January 3 1878 in Baltimore, Lenzberg began his career

accompanying dancing lessons at the piano. By 1903, with a couple of published compositions to his

credit, he got himself married and moved to New York City, eventually settling

in Queens. Thus began a long stint

serving as orchestra leader at various vaudeville houses in Manhattan and in

the summer, he led a band out on Long Island.

In 1919, Lenzberg

served as director of the George White Scandals of 1919 and also led the house

band at the Riverside Theater in New York. That year, Lenzberg

and the Riverside Orchestra began to make records for Edison, and though Lenzberg's

recording activity ended in 1922, he was prolific, ultimately producing more

than 50 sides for Edison. Lenzberg

continued to lead a band and appear on radio once it emerged, into the 1930s,

but the depression knocked him out of the performing end of the business. By

the last time Lenzberg

is heard from in the early 1940s, he was working as a booking agent. He passed away in April 1956.

However, here he is in a 1922 program, along with Horton's Ice Cream. Is that stuff still around?

However, here he is in a 1922 program, along with Horton's Ice Cream. Is that stuff still around?

Was this Julius's view as he crossed Broadway? Could be as this is circa 1920. The Riverside, Riviera and the Japanese Gardens all still have their original marquees, but the neon signs are new. Although William Fox (as in 20th Century) began construction of the Riverside, he gave it up to the uber powerful Keith people when they threatened him with no acts for his other theaters. The B. F. Keith people knew that 96th street was an ideal location; conveniently located with an express subway stop right there, you also have direct access to the New York Central Hudson River Railroad and the not yet covered over tracks at 96th street on the Hudson. Very important if you are moving a vaudeville show that often traveled as a package around the east coast, if not the country.

Notice that the 1923 Broadway View Hotel, known today as the place we all know and love, The Regent, does not appear to looming in the middle of Broadway as does today, placed perfectly where Broadway takes a bend to the west following the path of the old Bloomingdale Road.

More Tubby's Hook

Across the road from the Billings was this castle. Well it looked like a castle, in fact the nice reporter who, in 1921 while working for the New York Tribune, explored the upper reaches of this large out cropping of schist called it a "Norman structure, with its narrow windows and stone towers". So nice it was, it warranted it's very own post card. What it was called, according to the postcard, it was the Libby Castle. The "castle" had a larger claim to fame however as it was home to William Marcy Tweed, the Tammany Hall boss.

This is a later than the postcard picture, quite possibly very close to the end of the castle's existence. Tweed was living there when he was finally arrested for his unbridled corruption and fled from there to Spain. The land on which it stands was purchased in 1846 by Lucius Chittendon, a merchant from New Orleans whose name is all over the 1867 map, who got ninety-seven acres for $10,000. Angus C. Richards, another name all over the map (as A C Richards) bought a piece of the ground in 1855 and erected the castle, which in 1869 he sold to General Daniel Butterfield, who was acting for Tweed.

This is William Magear Tweed, a member of the Odd Fellows and the Masons, a volunteer firefighter, certified as an attorney, Commissioner of Public Works and the ring leader of one of the biggest centers of corruption ever to befall our great city - Tammany Hall. It had been said that Tweed put through Fort Washington Avenue and the Boulevard (Broadway) and Lafayette Boulevard which is now the Riverside Drive that feeds on to Dyckman Street from the Henry Hudson Parkway (part of which had been Riverside Drive). The reason he had these streets constructed was that Tweed wanted easy access to his home. Traveling up to what I have called Manhattan's border with Canada back in the post Civil War 19th century New York was not as easy or as fun as it is now. My street, west 104th between West End Avenue and Riverside was a dirt road until the early 1890's so one can imagine that streets up there were still on the back burner in regards to paving, sewers, waterlines, things of that nature.

However, poor Boss Tweed. The New York Times and the father of American political cartoons Thomas Nast were after him and caused a great deal of trouble. With such biting images how could he have not avoided trouble? Especially with that pesky New York Times turning down a $5 million bribe to not publish their findings of corruption and Harper's Weekly investigating why plastering at the new court house (which took 15 years to build) cost many thousands of dollars more than it was supposed too (kind of like the $600 toilet seat on the B-1 Bomber back in the '80's). He didn’t enjoy the castle for too long due to his legal entanglements. After serving a year in prison he fled to Spain in 1875 to avoid a civil suit brought on by New York State in an attempt to recover $6 million in embezzled funds. Only $6 million? They were being nice.

This was Tweed's home after his year as a guest of the State of New York. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison but a higher court reduced the sentence to one year. He had been convicted of only 204 of 220 criminal counts of extortion, bribery, embezzlement, ballot box tampering and general chicanery after all. He was re-arrested and then charged in a civil suit bought on by the City and the State of New York. Unfortunatly he was unable to come up with the $3 million in bail. However

Tweed had been allowed home visits and normally lived at the Ludlow Street Jail. The castle was in foreclosure as Tweed's son was behind in paying A.T. Stewart, the department store king. Tweed had put the names of various properties in the names of relatives, this house and his Metropolitan Hotel. Tweed, or should I say Tweeds, owed Stewart for the furnishings of the Metropolitan Hotel and the property is eventually lost.

However, incarceration was not for Mr. Tweed. As such a recognizable figure (after all Thomas Nast drew his portrait too many times) and even with all the scandal surrounding him, too much to go through here as there are entire books on the subject of Tweed and his shenanigans, he still had friends in high enough places in the business of law enforcement that saw no reason why this man should not be allowed out on weekends. After all, it wasn't like he killed anyone.

Sometimes the best intentions of mice and men go badly. Not wanting to pay the only $6 million the State was looking for, not having the $6 million the State was looking for, nor having any more desire for the structured life of prison, Mr. Tweed skipped bail. None of his friends knew where he could have possibly gone off to. However, one resident of Tubby's Hook did know.

When this particular resident of the banks of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek first appeared in the area is lost to the ages. He was living alone in a house on the banks by 1875. An anti-union "boatman", Civil War veteran and retired firefighter this man would become the unofficial mayor of the marshy shallows of the area then called “Cold Spring.” He had a couple of aliases, he was probably from the City of Brooklyn as he is listed as "Boatman" in the 1889-1890 Brooklyn directory. His name was Andrew Jackson "Pops" Seeley and rowed the about to be fugitive, William M. Tweed to a Spanish ship where he worked as a common seaman and eventually ended up heading to Spain. He almost made it into Spain but those darn cartoons came back to bite him; he was recognized from Nast's political cartoons and was turned over to an American warship which delivered him to the authorities in The City of New York on November 23, 1876, and he was returned to prison. Tweed knew the jig was up, he had lost. Broke, broken and desperate he now agreed to "turn state" about the corruption ridden Tammany Hall to a special committee set up by the Board of Alderman, in return for his release. However Governor Tilden refused to stick to the agreement, and Tweed remained in the Ludlow Street Jail where he died on April 12, 1878 from severe pneumonia and was buried in the Brooklyn's cemetery hot spot Greenwood. The Mayor at the time, Smith Ely, would not allow the flag at City Hall to be flown at half staff.

Friday, January 25, 2013

Tubby Hook - Who was Tubby? Inwood Part 1

By the late 18th century, after the revolution and naming and renaming streets and

places had begun, the area on this rock north of the village of

Manhattanville all the way to the top of the island was called Mount

Washington. It was the popular name anyway as it was also very

patriotic; after all George Washington did have 1 of his 9 major battles

in the area.

In 1921 the New York Tribune sent a reporter uptown to explore the rapidly developing hills of northern Manhattan and Washington Heights. At the time of her quest the area that was once the home of some of the wealthiest New Yorkers, that last bit of rural Manhattan was being swallowed up and absorbed into the city. The reporter, Eleanor Booth Simmons, went alone without a photographer. Even though there was much in the way of change happening there still was enough of the old to write about and she gives us quite a document of the still standing homes of once rich and powerful families including Nathan Straus, James Mcreery and C.K.G. Billings, to name a few.

This is from the 1867 map showing the north tip of Manhattan prior to the Harlem River Ship Canal cutting through and adding more acreage to the Bronx. The Harlem River flowed into a marsh and creek, then the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, .

As time marched on the upper section of the area close to the Hudson River became known as Tubby Hook, a name still used by a soon to be no longer dilapidated marina called the Tubby Hook Marina. But who was "Tubby" and why is there a hook named after him? The common theory behind the name lies with Dutch Sailors who, as they went up the Hudson called every point of land that stuck out into the river a "hook". Perhaps they saw in what was the bay of the Spuyten Duyvil creek a resemblance to a tub, with the steep wooded hills for sides. The actual hook is gone and so is the creek. The hook was just a bit north of the foot of Dyckman Street, but with all the land fill, the hook is now just part of Inwood Fields Park.

This is the same area but in 1897. The Harlem River Ship Canal has been cut through and a piece of Manhattan became part of the Bronx. Although still considered part of Manhattan by zip code and area code, the neighborhood of Marble hill looks like it is part of mainland United States. It also looks like wishful thinking to me, but there I go again being very boro-centric The path of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek that went around Marble Hill, making it a part of Manhattan Island and not part of the Bronx (or mainland United States), was filled in. The canal was widened along with what was left of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

"Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt was told he was crazy to invest in a railroad so far over on the west side of Manhattan. No one will use it he was told. "Build it and they will come" and by 1851 the railroad went all the way to Albany. Build a station and they will come is more like it. This the Inwood or Tubby Hook Station of the old Hudson River Rail Road. Once Vanderbilt consolidated his railroads into the uber railroad the New York Central, passenger service began to bypass the old passenger stations of the Hudson River Rail Road. The 1921 article points out that the "Old inhabitants say it was the policy of the New York Central that left Tubby Hook, as Inwood used to be called, in a forgotten pocket between two rivers, unpeopling the beautiful houses and abandoning them to ghosts". In 1871, with the opening of the first Grand Central Station, Vanderbilt connected the tracks of his Harlem River Rail Road with the tracks of the Hudson Line by building the Spuyten Duyvil - Port Morris Railroad so that trains leaving Grand Central could have easy access to the Hudson River Line. The old Hudson River Rail Road was used more and more for freight only. By the late 19th century only one or two slow locals served the passengers along this line and after the subway opened up there in 1905 the line was truly redundant. Not till 1900 did the first trolley cars run to Kingsbridge, and it was five years later when the subway was extended to Dyckman Street. For a good many years this most attractive part of Manhattan Island was rather inaccessible, except for the men who could afford their horses.

The postcard above correctly states that this is the Inwood Station of the N.Y. Central as this is after the Commodore consolidated his railroads. The Hudson River Railroad Station at Inwood, was also known as Tubby's Hook. In the above picture Dyckman Street is the street crossing the tracks, coming from the right and ending at the shore of the Hudson River which would be on the left. The road coming down the hill is River Road, later known as Bolton Road.

On one map the station is indicated as either "Inwood or Dyckman"

This is River Road / Bolton Road looking south towards the train station and the river. What all those guys are doing in that veranda is a mystery.

Way before the Titanic took them, way before they moved downtown to The Bloomingdale area, this was the home of Isidore and Ida Straus. Even with the over grown foliage of a front yard gone wild, one could tell that the home of Straus Family home must have been a swell place in its prime. However, by the time the Herald reporter made her trip to the area the house was in, as she put it, "a melancholy state of dilapidation". At the time the article was published, a policeman was living in it, and according to the article very happy to be there. "He is a fresh air enthusiast" the article went on, so much so that "he parked his two infant sons day and night for many months on the roof of the wide veranda". This is what attracted the Straus family to living way up in Tubby Hook as they too were fresh air enthusiasts. Isidore and Ida Straus were what we would now call "health nuts". However, rural splendor would eventually lose out to Ida's feeling cut off. This was not an especially easy area to get to.

This is the McCreery house, photographed in 1921. James McCreery was a successful dry goods dealer. So successful that he opened a behemoth department store on Broadway at 11th street (the building is still there - even after a bad fire in 1971 - as apartments).

To reach the McCreery house one had to take Dyckman Street to the end and then take a narrow path to River Road, a road that no longer exists. Walk north, past overgrown terraces and box hedges, and quaint houses with cupolas and pillars, with the river and the railroad tracks below. At the end of this narrow path, maybe wide enough for one car to negotiate it stood the house of James McCreery. At the end of what appears to be the path described there was a 20 acre estate owned by an E. Riggs. This site had a wooden house on it and would have western and northern views of the river (in addition to south and east) Basically where the tollbooths are now for the Henry Hudson Bridge. It is was not considered a beautiful building by the author of the article, calling it "high and square shouldered, it looks like a boarding house. But it commands a splendid view, and it has a generous air, as if it had tales to tell of the hospitality that once made it a social center."

Recognize this? If you take the north bound Henry Hudson past the George Washington Bridge on a stretch that was once Riverside Drive you have passed it. Constructed of Manhattan Schist quarried on site, this great arched stone gallery was the extravagant entry to the estate of Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings, a wealthy industrialist, noted eccentric and avid horseman.

Billings father was a major stockholder in the Peoples Gas Light and Coke Company. After college he joined this firm, that provided a lion's share of the gas for lighting to Chicago, eventually inheriting controlling interest in the company and, at the age of 40, retired from business to devote his time to his true love: the growing stable of horses he owned. In fact, he moved to New York and purchased acreage in this undeveloped area of uptown because of the recent opening of the Harlem River Speedway which ran from 155th street to Dyckman Street, where the elite would meet to compete, with their horses.

Another view of the driveway.

Like the postcard says, it was called Fort Tryon Hall. The "Hall" cost was $2,000,000 and stood on Manhattan's highest point, 250 feet above sea level, with 20-mile views of the Hudson Valley. His 25-acre estate encompassed formal gardens, a 126-foot-long bathhouse for the 75-foot indoor marble swimming pool, and a yacht landing on the Hudson at Dyckman Street. There he had his 232-foot yacht, Vanadis.

The road to the right is Margret Corbin Drive, the first woman to be wounded in battle during the American Revolution. "Captain Molly" as she became to be known, was from Kentucky and had followed her husband north. At the Battle of Washington Heights, November 16th 1776, "Captain Molly" took over her husband's cannon when he fell mortally wounded. The actual Fort Washington was further south between what is now 183rd and 185th streets. "Captain Molly" was severely wounded herself but recovered and after the war served as a domestic and cook. Always addressed as "Captain" she was reportedly "tart of tongue and sloppy in dress". She died in 1800 in Highland Falls New York. In 1926 the Daughters of the American Revolution had her remains moved to the Post Cemetery at West Point, one of the few women and maybe only one of two civilians to be interred there.

Originally from Chicago, in 1907, Billings, his wife, two children and 23 servants moved to a new residence described at the time as "In the style of Louis XIV", the house had several large towers, a Mansard roof along with the previously mentioned swimming pool, squash courts and maple lined bowling alleys.

This is the Gate keepers house at the end of Fort Washington Avenue. The gate was for Fort Tryon Hall. This little house was built in 1908, a year after the big house was completed. The gate house is till there, right at the entrance to the Heather Garden. The house serves as the office for the park administrator of Fort Tryon Park.

Billings and his family moved out. By 1916 he wanted to move on, not for any financial reason, he just wanted a change. He sold his 25 acre estate to John D. Rockefeller Jr. for $875,000. This sale began what we all know and love today, Fort Tryon Park. Unfortunatly Fort Tryon Hall is gone, it burned down in 1926 after being spared the wrecker's ball. Preservationists protested the destruction of the house and the city turned down John D. Rockefeller Jr's offer of a new park; the city knew he wanted to have some streets closed on the East Side for his Rockefeller University (but this is another story) so the quid pro quo situation would have to wait, as would the park and the house was saved for a while. This practically a chateau house only lasted 19 years but his 232-foot yacht, Vanadis, still exists. It is now anchored at Riddarholmen in Stockholm. It is being used as a hotel known as Mälardrottningen.

In 1921 the New York Tribune sent a reporter uptown to explore the rapidly developing hills of northern Manhattan and Washington Heights. At the time of her quest the area that was once the home of some of the wealthiest New Yorkers, that last bit of rural Manhattan was being swallowed up and absorbed into the city. The reporter, Eleanor Booth Simmons, went alone without a photographer. Even though there was much in the way of change happening there still was enough of the old to write about and she gives us quite a document of the still standing homes of once rich and powerful families including Nathan Straus, James Mcreery and C.K.G. Billings, to name a few.

This is from the 1867 map showing the north tip of Manhattan prior to the Harlem River Ship Canal cutting through and adding more acreage to the Bronx. The Harlem River flowed into a marsh and creek, then the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, .

As time marched on the upper section of the area close to the Hudson River became known as Tubby Hook, a name still used by a soon to be no longer dilapidated marina called the Tubby Hook Marina. But who was "Tubby" and why is there a hook named after him? The common theory behind the name lies with Dutch Sailors who, as they went up the Hudson called every point of land that stuck out into the river a "hook". Perhaps they saw in what was the bay of the Spuyten Duyvil creek a resemblance to a tub, with the steep wooded hills for sides. The actual hook is gone and so is the creek. The hook was just a bit north of the foot of Dyckman Street, but with all the land fill, the hook is now just part of Inwood Fields Park.

This is the same area but in 1897. The Harlem River Ship Canal has been cut through and a piece of Manhattan became part of the Bronx. Although still considered part of Manhattan by zip code and area code, the neighborhood of Marble hill looks like it is part of mainland United States. It also looks like wishful thinking to me, but there I go again being very boro-centric The path of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek that went around Marble Hill, making it a part of Manhattan Island and not part of the Bronx (or mainland United States), was filled in. The canal was widened along with what was left of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

"Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt was told he was crazy to invest in a railroad so far over on the west side of Manhattan. No one will use it he was told. "Build it and they will come" and by 1851 the railroad went all the way to Albany. Build a station and they will come is more like it. This the Inwood or Tubby Hook Station of the old Hudson River Rail Road. Once Vanderbilt consolidated his railroads into the uber railroad the New York Central, passenger service began to bypass the old passenger stations of the Hudson River Rail Road. The 1921 article points out that the "Old inhabitants say it was the policy of the New York Central that left Tubby Hook, as Inwood used to be called, in a forgotten pocket between two rivers, unpeopling the beautiful houses and abandoning them to ghosts". In 1871, with the opening of the first Grand Central Station, Vanderbilt connected the tracks of his Harlem River Rail Road with the tracks of the Hudson Line by building the Spuyten Duyvil - Port Morris Railroad so that trains leaving Grand Central could have easy access to the Hudson River Line. The old Hudson River Rail Road was used more and more for freight only. By the late 19th century only one or two slow locals served the passengers along this line and after the subway opened up there in 1905 the line was truly redundant. Not till 1900 did the first trolley cars run to Kingsbridge, and it was five years later when the subway was extended to Dyckman Street. For a good many years this most attractive part of Manhattan Island was rather inaccessible, except for the men who could afford their horses.

The postcard above correctly states that this is the Inwood Station of the N.Y. Central as this is after the Commodore consolidated his railroads. The Hudson River Railroad Station at Inwood, was also known as Tubby's Hook. In the above picture Dyckman Street is the street crossing the tracks, coming from the right and ending at the shore of the Hudson River which would be on the left. The road coming down the hill is River Road, later known as Bolton Road.

On one map the station is indicated as either "Inwood or Dyckman"

This is River Road / Bolton Road looking south towards the train station and the river. What all those guys are doing in that veranda is a mystery.

Way before the Titanic took them, way before they moved downtown to The Bloomingdale area, this was the home of Isidore and Ida Straus. Even with the over grown foliage of a front yard gone wild, one could tell that the home of Straus Family home must have been a swell place in its prime. However, by the time the Herald reporter made her trip to the area the house was in, as she put it, "a melancholy state of dilapidation". At the time the article was published, a policeman was living in it, and according to the article very happy to be there. "He is a fresh air enthusiast" the article went on, so much so that "he parked his two infant sons day and night for many months on the roof of the wide veranda". This is what attracted the Straus family to living way up in Tubby Hook as they too were fresh air enthusiasts. Isidore and Ida Straus were what we would now call "health nuts". However, rural splendor would eventually lose out to Ida's feeling cut off. This was not an especially easy area to get to.

This is the McCreery house, photographed in 1921. James McCreery was a successful dry goods dealer. So successful that he opened a behemoth department store on Broadway at 11th street (the building is still there - even after a bad fire in 1971 - as apartments).

To reach the McCreery house one had to take Dyckman Street to the end and then take a narrow path to River Road, a road that no longer exists. Walk north, past overgrown terraces and box hedges, and quaint houses with cupolas and pillars, with the river and the railroad tracks below. At the end of this narrow path, maybe wide enough for one car to negotiate it stood the house of James McCreery. At the end of what appears to be the path described there was a 20 acre estate owned by an E. Riggs. This site had a wooden house on it and would have western and northern views of the river (in addition to south and east) Basically where the tollbooths are now for the Henry Hudson Bridge. It is was not considered a beautiful building by the author of the article, calling it "high and square shouldered, it looks like a boarding house. But it commands a splendid view, and it has a generous air, as if it had tales to tell of the hospitality that once made it a social center."

Recognize this? If you take the north bound Henry Hudson past the George Washington Bridge on a stretch that was once Riverside Drive you have passed it. Constructed of Manhattan Schist quarried on site, this great arched stone gallery was the extravagant entry to the estate of Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings, a wealthy industrialist, noted eccentric and avid horseman.

Billings father was a major stockholder in the Peoples Gas Light and Coke Company. After college he joined this firm, that provided a lion's share of the gas for lighting to Chicago, eventually inheriting controlling interest in the company and, at the age of 40, retired from business to devote his time to his true love: the growing stable of horses he owned. In fact, he moved to New York and purchased acreage in this undeveloped area of uptown because of the recent opening of the Harlem River Speedway which ran from 155th street to Dyckman Street, where the elite would meet to compete, with their horses.

Another view of the driveway.

Like the postcard says, it was called Fort Tryon Hall. The "Hall" cost was $2,000,000 and stood on Manhattan's highest point, 250 feet above sea level, with 20-mile views of the Hudson Valley. His 25-acre estate encompassed formal gardens, a 126-foot-long bathhouse for the 75-foot indoor marble swimming pool, and a yacht landing on the Hudson at Dyckman Street. There he had his 232-foot yacht, Vanadis.

The road to the right is Margret Corbin Drive, the first woman to be wounded in battle during the American Revolution. "Captain Molly" as she became to be known, was from Kentucky and had followed her husband north. At the Battle of Washington Heights, November 16th 1776, "Captain Molly" took over her husband's cannon when he fell mortally wounded. The actual Fort Washington was further south between what is now 183rd and 185th streets. "Captain Molly" was severely wounded herself but recovered and after the war served as a domestic and cook. Always addressed as "Captain" she was reportedly "tart of tongue and sloppy in dress". She died in 1800 in Highland Falls New York. In 1926 the Daughters of the American Revolution had her remains moved to the Post Cemetery at West Point, one of the few women and maybe only one of two civilians to be interred there.

Originally from Chicago, in 1907, Billings, his wife, two children and 23 servants moved to a new residence described at the time as "In the style of Louis XIV", the house had several large towers, a Mansard roof along with the previously mentioned swimming pool, squash courts and maple lined bowling alleys.

This is the Gate keepers house at the end of Fort Washington Avenue. The gate was for Fort Tryon Hall. This little house was built in 1908, a year after the big house was completed. The gate house is till there, right at the entrance to the Heather Garden. The house serves as the office for the park administrator of Fort Tryon Park.

Billings and his family moved out. By 1916 he wanted to move on, not for any financial reason, he just wanted a change. He sold his 25 acre estate to John D. Rockefeller Jr. for $875,000. This sale began what we all know and love today, Fort Tryon Park. Unfortunatly Fort Tryon Hall is gone, it burned down in 1926 after being spared the wrecker's ball. Preservationists protested the destruction of the house and the city turned down John D. Rockefeller Jr's offer of a new park; the city knew he wanted to have some streets closed on the East Side for his Rockefeller University (but this is another story) so the quid pro quo situation would have to wait, as would the park and the house was saved for a while. This practically a chateau house only lasted 19 years but his 232-foot yacht, Vanadis, still exists. It is now anchored at Riddarholmen in Stockholm. It is being used as a hotel known as Mälardrottningen.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)