“Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? . . . this is the time to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won’t all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes.” - Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Sunday, April 1, 2012

What am I doing on the East Side?

Every Wednesday up until recently, I passed two wood frame houses, relics of another time. A pre - 1877 time as this was the year the City of New York passed a ban on this type of construction over safety concerns. In an era of wood construction, New York has some pretty disastrous fires: The Great Fire of 1776 (which may have been started by Nathan Hale and a book of matches) and the pretty good fire of 1835. Both of these fires destroyed thousands of wooden structures (ever wonder why we have nothing left from the Dutch era in lower Manhattan?) and our forward thinking city fathers were looking out for our well being. This house went up in 1859 at what is now 122 East 92nd. It was built for a customs house officer by the name of Andrew C. Flanagan. The area had undergone a population boost when the first railroad in Manhattan, the Harlem River Railroad, opened a station at 86th and Fourth (Park) Avenue in 1836.

An addition was built for the servants and is visible on the far left, a slender portion that is set back from the original facade. In the 1920's, a fourth floor was added and the original columns on the porch had to be replaced. It is still a single family home.

In 1870 Mr. Flanagan sold the western edge of his property and by 1871 number 120 East 92nd was built. It too is still single family. Both of these structures represent eras so by gone in this town it shocks me that they and the others like it that have survived north of Greenwich Village: The rural character of the Yorkville area is exemplified by 122 East 92nd, with it's deep porch and large french door/windows that lead out to that porch as well as the construction method - wood.

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

The birthplace of a of song title.

This is the south east corner of 11th street and 6th Avenue in 1911, before it was renamed "Avenue of the Americas. These wood frame structures predate the civil war. The building on the corner was and always had been a saloon. A real sawdust on the floor type of dive under the shadow of the 6th Avenue El. The saloon predated the El and was a very much a local place where everybody knew your name. Gossip was exchanged, people drank, people settled conflicts in various ways. However it was during the Civil War that this tavern found it's way into immortality. In New York, while north of the Mason - Dixon Line, there were those harbored sympathy for the Southern cause. It boiled down to this: If the price of cotton goes up, it will affect a bottom line. The south was the producer of cotton and northern textile firms were the major buyers. In addition to having a business world interest in the war, the notoriously corrupt mayor at the time, Fernando Wood, made no secret of where his sympathies lied. Mayor Wood, buy the way, had a summer residence around 75th street and Bloomingdale Road.

These wooden structures were gone by 1915. On the far left of the top picture is is the still extant Second Cemetery of Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue, Shearith Israel. The First Cemetery is still down next to Chatham Square.

The “Grapevine”, according to legend, was a popular spot amongst southern spies, Union officers who were spying on the southern spies, and many incognito newspaper reporters.

Of course everyone knew that the locals would go drink, gossip and eavesdrop on conversations there, so the tavern became known as the place where many rumors originated. This became the origin of the phrase “heard it through the grapevine”. The newspapers began using this phrase which became part of the local dialect. Skip ahead to 1966, a song is written by Barret Strong and Norman Whitfield for Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. Barret Strong was a singer with one hit (Money - That's What I Want) and could not find a follow up. The old phrase was incorporated into one of the most famous American Pop songs of all time by local resident Whitfield.These wooden structures were gone by 1915. On the far left of the top picture is is the still extant Second Cemetery of Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue, Shearith Israel. The First Cemetery is still down next to Chatham Square.

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

The Doctor's Summer Home - Broadway and 94th Street

This is Doctor Valentine Mott. Born in Glen Cove Long Island in 1785, the good doctor went on to be called, some circles, the father of American vascular surgery. He was an artist and a pioneer on this new frontier of surgery. He was a firm believer in anesthesia, which he championed stating that "pain is the only evil" and that anesthesia was safe if administered correctly. Doctor Mott was also ambidextrous, a helpful trait in the pre-anesthesia world of surgery. You wanted a surgeon who was good with both hands at the same time as it sped up the procedure. Although there is a Mott Street here in Manhattan, it is named after Joseph Mott, a local butcher and tavern owner who provided support to the patriots during the American Revolution. Doctor Mott, though, did all right.

This is the doctor's summer home. Although the Mott's owned a still extant townhouse at 1 Gramercy Park, this is where he spent a few summers. The village of Bloomingdale retained it's rural character even after the Civil War. The house, built in 1835, was located on approximately 93rd and the middle Broadway. If this is the Bloomingdale Road, as I believe it is, the house faced east, we (and Victor Prevost who took the picture) are facing west. This view was taken in 1853.

Monday, February 27, 2012

The Academy of Music otherwise known as The Palladium

In 1854 New York's first successful large scale opera house opened on the north side of 14th street at the intersection with Irving Place. There had been opera houses before, but not with a capacity of 4000 seats. There had been the Italian Opera House built in 1833 by Lorenzo Da Ponte as a home for his new New York Opera Company, which lasted only two seasons. In 1847, the Astor Opera House opened on Astor Place, only to close several years later after the infamous riot provoked by competing performances of Macbeth by English actor William Charles Macready at the Opera House and American Edwin Forrest at the nearby Broadway Theatre. After the Metropolitan Opera House established itself as the opera house in New York in 1883, the Academy of music stopped presenting opera in 1886. The Academy of Music was not long for this world or 14th street. After being taken over by William Fox, the old Academy, with it's 5 balconies, went legit for a while then Vaudeville, then movie and Vaudeville. Then Con Ed (who owned the land that the theater and it's neighbor Tammany Hall were on) expanded it's headquarters. The Academy was demolished in 1926.

William Fox knew what was coming and purchased a plot across 14th Street, hired his (and mine) favorite architect, Thomas Lamb and opened a 3600 seat theater “Built to withstand the Ages— Dedicated to future generations,” as the publicity stated. This picture is from 1931 and vaudeville is still a feature at the Academy of Music. The marquee advertises the appearance of Barto and Mann. Dewey Barto (1896–1973) and George Mann (1905 — 1977) were a comedic dance act known as the "laugh kings" of vaudeville. From the late 1920s to the early 1940s Barto and Mann toured the country and every marquee with their name on it was photographed by George Mann. Their acrobatic, somewhat risqué, performance played on their disparities in height; Barto was 4'11" and Mann was 6'6. Dewey Barto was Nancy Walker (Rhoda's TV mother) father.

The lobby just after opening in 1926.

House left. This must be one of the first houses Thomas Lamb designed that did not include boxes. His Loew's 83rd Street built the same year did have boxes and was built for the same purpose, movies and vaudeville. All the way over on the left side of the pit there appears to be a Mighty Wurlitzer which ultimately fell into disrepair but was restored and played on October 28th, 1968 in what was billed as "Sounds Of The Silents". The organ had been restored by The Theater Organ Society of New York. The Academy opened with a 60 piece orchestra to play for the feature picture as well as the show.

This is house left again from the balcony.

From 1964 through 1978 the Academy became a rock venue. During this time, the Academy became less and less of a first run house and finally stopped showing movies by 1975. During the day the bill included double and triple features of kung fu pictures. In 1971 the Fillmore East closed and the Academy was born again as the premire smaller than Madison Square Garden venue for rock music shows. Everyone played here, from the Beach Boys, Rolling Stones, Yes, Fleetwood Mac, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, The Band, even AC/DC had their American debut here. The name change to Palladium came in 1976.

January 7th, 1978 to be specific. The downtown location made this house the ideal location for this show.

And this one too. This must have been an incredible show.

Progress? In 1985 after being forced to sell their Studio 54, Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell converted the Palladium into a night club. Architecture firm Arata Isozaki & Associates redesigned the space.

The Dome looking towards where the stage used to be.

What was left of the old Academy was restored but it was blocked by the improvements. In 1998 the Palladium closed, was sold to NYU and was demolished the Academy of Music and replaced it with Palladium Hall, a dormitory.

Thursday, February 16, 2012

Destruction leads to revelation

I am so glad I got a smart phone with a good camera. This is on 125th street back on January 8th 2012. I am facing north and the building on the north side of 125 has recently come down. The demolition revealed this advertisement for Theo. F. Tone & Co. It seems they sold coal and that they had a Harlem office. The right half of the ad indicates that they had a yard on 12th avenue on what looks like 133rd street. This makes sense as 12th avenue would be next to the Hudson River which would be the way large amounts of coal could be delivered to a distribution point. This is similar to the coal faciltiy on 96th street and Riverside pictured below (as a reminder of what used to be before Robert Moses put the West Side Highway there). The ad was painted on the entire east facing wall and it appears to have covered up an earlier ad.

Friday, February 3, 2012

42nd Street and the theater with 3 names over 80 years.

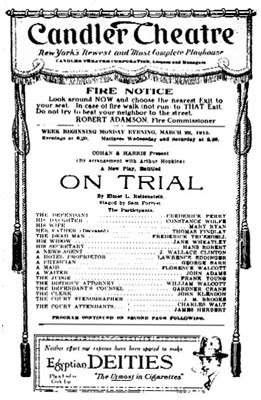

As 42nd Street was becoming the "Avenue I'm taking you to", the center of the theater district that migrated up Broadway since the 18th century, there were those who believed that this street could also be home to business (other than show) development. In this case a speculatively built 24 story white Terra cotta office tower skyscraper that ultimately nodded to the neighborhood by including a theater. This gleaming white tower was built by the Coca Cola Company and opened in 1913. For a brief period it was the tallest structure in New York north of 24th street (the Metropolitan Life tower in Madison Square was the tallest building in the world from 1909 until 1913 when the Woolworth Building opened). The person behind this plan was Asa Griggs Candler who purchased a failing soft drink company in 1891 for $2300. By 1917 Coca Cola was the world's most recognized trademark. And Candler joined other out of state investors in improving our skyline (the Flatiron Building for example was built by foreign money - all the way from Chicago) by adding his New York office here on "The Deuce". Not satisfied with his name on the door to the building, he got his name on a marquee. The Candler Theater was designed by, who else, Thomas Lamb.

You entered on 42nd street but the theater itself was on 41rst street. This is the same set up for the New Amsterdam which was just to the east and the Liberty Theater which was to the west of the Candler. What this meant was when you went to one of these theaters you had to walk down a long narrow lobby to get to the theater. The main reason for this was that the land was cheaper on 41rst and 43rd streets (because this happened on the north side of 42nd as well) and more theaters could be built if there was a sort of alternation between one theater on 41rst and the next on 42nd. The Eltinge Theater, when it was in it's original location, stood infront of the Liberty Theater's auditorium. Both theaters were entered from 42nd but the Eltinge was really on 42nd. In addition to the land being a cheaper purchase, the taxes on the 41rst and 43rd street parcels, usually the larger structure, would be lower. This fact played a role in determining the future of 42nd street as the grip of the Great Depression took hold.

The candler was finished by May of 1914 but the first production to open was on August 19th, 1914 was The Trial by Elmer Rice. Presented by the producing team of Sam H. Harris and George M. Cohan the production ran a respectable 365 performances.

This was the second production in the Candler which ran 245 performances. Look at those prices. What is even more shocking is that people made money with runs lasting 245 performances before the show would go on the road. In 1916 the Candler was renamed the Cohan & Harris Theater. In 1921 Cohan left the partnership and the Cohan & Harris became just the Harris Theater. This was the name of the theater for the rest of it's existence. In 1922, theater history is made with Tyrone Power Sr. as Claudius King of Denmark and John Barrymore as Hamlet in a limited run revival (aren't all Shakespeare productions revivals?). John Barrymore broke the record for playing Hamlet 101 nights in a row, the run was 101 performances. The previous record was set Edwin Booth of only a mere 100 nights in a row.

This behind the orchestra section. The ceiling of the 1200 seat house contained an elliptical shallow dome, ringed by Art-Nouveau style chandeliers in a floral theme, not unlike those at the New Amsterdam next door. With one balcony and boxes on either side of the proscenium arch, the Italian Baroque auditorium included gilded plasterwork around the proscenium and a general color scheme of ivory and gold. Its 25-foot wide marble lobby had 17th Century style wall panels, decorated in floral patterns (floral patterns seemed to have been a theme running throughout the house). Its foyers were decorated with tapestries depicting scenes from Shakespeare.

The last live production at the Harris opened January 16th 1933 and ran for 70 performances. Not too good. The play in one act was written and produced by George M. Cohan. When this production moved out in March of 1933, movies moved in for good. This appears to be what the movie screen set up looked like when the change over happened. The Candler was built with a projection booth so the change over was not so dramatic. Only when movies went wide screen after 1953 was there a need to alter the decor by removing the boxes or other similar "improvements". So for 61 more years, the Harris remained a 42nd Street triple feature grind house, losing most of its original décor, including the tapestries, the chandeliers, and the side boxes during that time.

This is how most of us remember the Harris. The theater went dark forever in 1994 although there were hopes that the magic of Disney that took over the severely scarred New Amsterdam would happen here. No such luck as it was demolished in 1996 to make room for Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum.

Monday, January 30, 2012

Oldest Photograph of New York - The Mystery of the Location.

This is possibly the oldest photograph, actually a Daguerreotype, of New York City. I have enhanced this image to provide greater detail. The original sold for $62,500 at an auction at Sotheby's in March of 2009. The photo was found at a small auction in New England with the following handwritten note attached:

This view, was taken at too great a distance, & from ground 60 or 70 feet lower than the building; rendering the lower Story of the House, & the front Portico entirely invisible. (the handsomest part of the House.) The main road, passes between the two Post & rail fences. (called, a continuation of Broadway 60 feet wide.) It requires a maganifying glass, to clearly distinguish the Evergreens, within the circular enclosure, taken the last of October, when nearly half of the leaves were off the trees.

May 1849. L. B.So does this mean it is 1848? More importantly, were on the Bloomingdale Road is it?

This is one possibility, this might be the house in the photo. This photo is from about 1902 of a house on the east side of Broadway between 100th and 101rst Streets. Broadway had only been called Broadway north of 59th street for 3 years, prior to that it was called "The Boulevard". The Bloomingdale Road, a road that was, for the most part, absorbed into the grid of 1811, ran just east of the current Boulevard and the even more current Broadway. The house at the time of this photo was the residence of Reverend J. Peters. It was replaced by Emory Roth's 210 West 101rst Street.

Notice the 5 widows across the second floor.

This is a map from 1867 which clearly indicates the Bloomingdale Road. Along the Road, between 101rst and 100th streets, in between the properties labeled "Peters" and "Jackson", there is a structure. Obviously the Reverend Peters owned the house and the land in 1867. The Boulevard or Broadway of the future is indicated by a shaded in road (or avenue for lack of better description).

This is a map from 1897. The house is very close to The Boulevard, it is yellow indicating that it is a wooden frame structure. It is located in block number 1872 and has a "46" on it. The blue lines to the right are the old boundary lines of the Bloomingdale Road.

Now the 1902 picture of the house clearly shows the front of the house. The house front faces west. Why? The view was better, you could probably see the river from the front porch when this house was built. If the photograph was taken from the east side of the Bloomingdale Road then we are seeing the back of the house. This has to be were the daguerreotype was taken from, east of the road facing west. The location of the road in relation to the house in the 1867 map matches that of the daguerreotype. Even with the indication on the map of 1867 of more structures in the area than in the daguerreotype, the development is still sparse. In addition there is a 19 year difference from the daguerreotype to the map and things change in this town over almost 2 decades. As for the hill, New Yorkers have been leveling this island since the Dutch showed up in 1609, so a more dramatic hill in 1848 is not unusual. The topography has changed on this rock so much that I can accept an uphill slope towards the west from somewhere in the middle of or just east of what is now Amsterdam Avenue.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)